MagazinePeter Matthiessen’s HomegoingBy JEFF HIMMELMAN APRIL 3, 2014

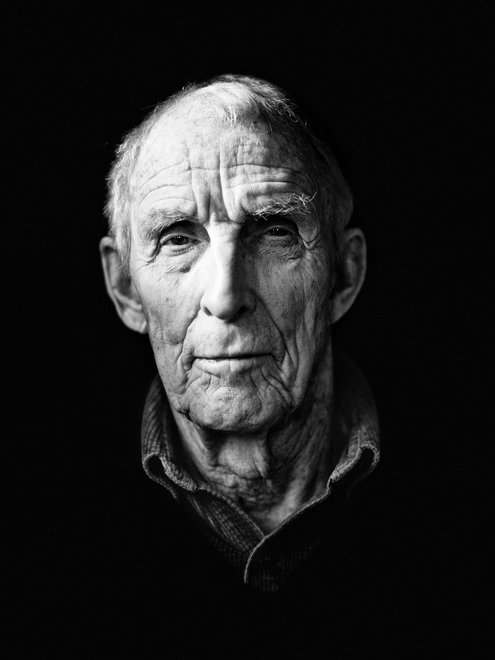

Peter Matthiessen, at home in March. Credit Damon Winter/The New York Times Out the Montauk Highway, south toward the water, then a quick right before the beach and you’re there, at the Sagaponack house where the author and Zen teacher Peter Matthiessen has lived for the last 60 years. The home used to be the garage and outbuildings of a larger estate, and there is an improvised, of-the-earth sprawl to the place. One side of the main house is grown over with ivy, and under the portico, in between two piles of chopped firewood, an immense finback whale skull balances on blocks. Just to the left of the front door sits a tree stump covered stupalike with shells and other found objects. After I ring the doorbell and rap a few times on the glass, Matthiessen emerges from his living room and waves me in.

He has spent much of his career going back in time — up to ancient villages in the remote reaches of the Himalayas, out to the vast plains of Africa in search of the roots of man — but now time has caught up to him. He’s 86, and for the last 15 months he has been countering leukemia with courses of chemotherapy. You can still see the intensity in his long, serious face and clear blue eyes, but there is an unexpected softness to him as he pads back toward the living room in an old sweater and stockinged feet. His latest novel, “In Paradise,” is being promoted by his publisher as his “final word,” but Matthiessen doesn’t want to talk about the book or his career in those terms. He has no desire for sympathy points. Though he did not want to dwell on it, he acknowledged that his medical situation was “precarious,” and a few weeks after our two days together his health would decline to the point that he had to be admitted to a hospital, with family standing by. It gave our conversations the feeling of stolen time.

Matthiessen, seated at center in dark sweater, on a Harvard-Peabody Expedition in New Guinea in 1961, with Michael Rockefeller at his left. Credit Eliot Elisofon/Peabody Museum of Achaeology and Ethnology

Though Matthiessen is not as well known as some other names of his generation, you would be hard-pressed to find a greater life in American letters over the last half-century. He is the only writer ever to win the National Book Award for nonfiction and fiction, but it’s not just the writing: Born into the East Coast establishment, Matthiessen ran from it, and in the running became a novelist, a C.I.A. agent, a founder of The Paris Review, author of more than 30 books, a naturalist, an activist and a master in one of the most respected lineages in Zen. As early as 1978, he was already being referred to, in a review in The New York Times, as a “throwback,” because he has always seemed to be of a different, earlier era, with universal, spiritual and essentially timeless concerns.

These concerns are evident throughout his house. In the living room, on the wall behind the piano, is a set of photographs from an expedition Matthiessen undertook to New Guinea with Michael Rockefeller in 1961, a trip that Matthiessen would turn into “Under the Mountain Wall” (1962). As we stood in front of the images — tribal boys throwing spears through a hoop hurled aloft, warriors approaching one another in aggression — Matthiessen mentioned that a recent book by the journalist Carl Hoffman confirmed his suspicions that Rockefeller was killed and eaten by Asmat warriors on a later expedition. It was a reminder of the extremity of his serial travels. On the other side of the room, behind a well-stocked bar, is a small study, where Matthiessen showed me two framed photographs: on the left, two slender young men in bathing suits; on the right, an aged Matthiessen holding a wooden box in his hands. “That’s me and Bill Styron on a dock in Italy,” he said. “We were drunk. That was right before I left the C.I.A.” Then, pointing at the other: “And that’s me with Bill’s ashes.”

Matthiessen’s family is descended from Friesian whalers; he notes, with some pride, that one of his ancestors is name-checked in “Moby-[banned term].” He was sent to St. Bernard’s, Greenwich Country Day School, Hotchkiss and Yale, and you can feel all of that breeding in his mannerisms and speech, as much as he might later have tried to forsake it. Yet despite the privilege, Matthiessen has referred in his work to an unspecified rage and pain that he felt as a young man, which led him to rebel against authority throughout his adolescence and then to experiment later with psychedelic drugs and meditation.

“I was so angry,” he told me. “I was constantly in a contest — not a contest, but with my father.” We were sitting in his living room, flanking a picture window that looks out over the yard. Matthiessen’s father, Erard, was a successful architect who later in life became interested in conservation. “He was a wonderful man, and I ended up devoted to him, but it wasn’t so good,” Matthiessen said. “I was always in trouble, constantly in trouble. I was combating the world.”

After graduating from Yale in 1950, Matthiessen became engaged to Patsy Southgate, a Smith graduate whose father had been the chief of protocol in Roosevelt’s White House. Southgate was famously attractive and energetic; The Times, in her obituary in 1998, noted without irony that she was “renowned as the most beautiful woman in Paris.” Matthiessen made what he calls “an utter shambles” of their engagement party that summer, behaving so badly that “people still talk about it,” and then he left the next morning on a birding expedition without saying sorry or goodbye. “I was being sucked into the system before I was ready,” he said. “I hadn’t had the adventures, the travel.”

Southgate called off the engagement, but he eventually won her back — “She was worth fighting for” — in part by securing a job with the C.I.A. that would send them both back to Paris. “I didn’t know anything when I went over there,” he said of his posting. “In those days, it was considered a patriotic act, to spy for your country. People were scared of the Cold War. You can’t blame them — everybody brandishing nukes. And here I am, a young Yalie, I’m always in the club drinking martinis, what did I know from politics?” It’s his standard explanation for how it happened, and though it imputes a high degree of naïveté to an already fiercely intelligent and independent young person, in its way it seems true enough. The C.I.A. wasn’t yet what it would become. “I’d started a first novel, and I had no way to pay for it,” Matthiessen said. “I was being urged to do something for my country, which appealed to my patriotic thing. I thought it was an ideal situation. And they also told me I would hardly have to do any work at all, that I would have plenty of time for my own.”

He was assigned to keep his eye on communist “enemies,” who were, he said, “out on the street corners peddling L’Humanité,” the party newspaper. In his spare time, he worked on his fiction. There was a healthy community of American expatriate writers in Paris in the early ’50s, just as there was after World War I, among them Terry Southern, Doc Humes and William Styron, who had early success with his first novel, “Lie Down in Darkness.” Matthiessen befriended them, and out of several late-night conversations with Humes came the idea for a new literary magazine. Matthiessen wasn’t sure that Humes was up to the task of running it, so he called his childhood friend George Plimpton, who was then at Cambridge. Plimpton soon arrived in Paris and became the first editor of The Paris Review, a position he would hold for 50 years.

Matthiessen has been frank about his motivation for starting the magazine. As he told Nelson Aldrich Jr., for “George, Being George,” an oral history of Plimpton: “I needed more cover for my nefarious activities, the worst of which was the unpleasant task of checking on certain Americans in Paris to see what they were up to. My cover, officially, was my first novel, but my contact man . . . had said, ‘Anything else you can do while you’re here?’ I could now say, ‘Well, yes, I’m an editor on a magazine.’ ” When Matthiessen eventually decided years later to tell Plimpton the truth, Plimpton was “shocked and very angry, understandably so,” Matthiessen told Aldrich. “Who, after all, wants to hear that the ‘love of his life,’ as he himself would call it, had been conceived as a cover for another man’s secret activities?”

Matthiessen’s double life in Paris would come to an end in 1953. He began to be disillusioned by the C.I.A., which in his estimation was filled mostly with Ivy League stuffed shirts who didn’t know or care anything about the poor people whom the communists were trying to reach. He was also repelled by the anticommunist witch hunts taking place in the United States. The environment as a whole “pushed me leftward,” as he put it. He has said that his stint as a spy was the only of his life’s adventures that he regrets.

After quitting the C.I.A., Matthiessen returned to America with Patsy and soon settled in Sagaponack, where he would supplement his writing income with commercial fishing. He described those early years on Long Island as the happiest of his life, “when I was writing but also doing hard physical labor.” He referenced a line from Turgenev a few times, from the suicide note of a character named Nejdanov: “I could not simplify myself.” “That really struck home,” Matthiessen said. “I knew exactly what he means.” He paused and then whispered it again. “ ‘I could not simplify myself,’ ” and then he added, “That’s always been my goal.”

- Quote :

- He has said that his stint as a spy was the only of his life’s adventures that he regrets.

Over the next 15 years, Matthiessen would produce four novels — including “At Play in the Fields of the Lord” (1965), his first commercial success — and six books of nonfiction, most based on his far-flung expeditions, from New Guinea to the remote forests of South America. He and Southgate divorced in 1956, and in 1963 he married the writer Deborah Love, a spiritual seeker as he was. He’d already taken ayahuasca in the South American wilderness, an episode he transmutes memorably into fiction in “At Play,” and with Love, he would turn to other psychedelic drugs and a bizarre LSD-driven form of therapy. In August 1968, returning from a seven-month trip to Africa that would become a part of “The Tree Where Man Was Born” (1972), Matthiessen arrived at home to find three Japanese Zen masters standing in his driveway. They were visiting Love, who had become a Zen student while Matthiessen was away on expeditions. He likes to joke that they took one look at him, saw how deluded he was, then immediately felt sorry for his wife. A year or so later, one of those teachers, the enigmatic and charismatic Soen Nakagawa, would accept him as a student.

Matthiessen’s turn to Zen was directly responsible for the two best books he has written (and maybe three, if you count “The Tree Where Man Was Born,” which he finished after becoming a student). “The Snow Leopard” (1978), Matthiessen’s account of his journey high into the Himalayas, and the finely wrought, poetic novel “Far Tortuga” (1975), represent the height of his craft as a writer. “The Snow Leopard” is almost entirely about Zen, and “Far Tortuga,” plainly Matthiessen’s favorite book, grew out of his practice in a different way. “It was the most exhilarating book I’ve ever written,” he told an interviewer for The Paris Review in 1999. “More than anything I’ve done, perhaps, ‘Far Tortuga’ was influenced by Zen training. The grit and feel of this present moment, moment after moment, opening out into the oceanic wonder of the sea and sky.”

Such talk can be hard to parse, which is why Matthiessen usually avoids it. “I don’t love talking about Zen,” he told me. “Somebody says, ‘So what is Zen, anyway?’ Often with a note of hidden hostility. And you try to explain, and then it’s, ‘Oh, [banned term], what am I saying?’ ” He laughed and then mimed shooting his own head off. But as the Zen master Dainin Katagiri once said, “You have to say something.” So: The heart of Zen is the practice of zazen — seated, silent meditation — which is based predominantly on bringing your attention to the present moment (often via concentrating on your breath) and then doing your best to keep it there. The extension of that practice to life off the cushion is fairly straightforward: When you’re listening, really listen; when you’re eating, just eat. Pay attention to what you’re doing. There are more advanced practices, of course, and the particular tradition that Matthiessen studied in his early days was a rigorous form called Rinzai, which is noted for its intense focus on

kensho, or sudden enlightenment.

Starting when he was 43, Matthiessen spent a full week several times a year in

sesshin, a retreat in which he and other students sat zazen for as many as 14 hours a day. He was extraordinarily devoted. Something about the intensity and formality and even the pain of Zen appealed to him. (The cross-legged positions are painful for everybody, and an oft-recycled quote holds that “pain in the legs is the taste of zazen.”) In regular interviews with the teacher, called

dokusan, the student is able to test his understanding, and there is a confrontational element that also fits with Matthiessen’s nature. The structures — robes, chanting, bowing, long periods of silence — can seem rigid and foreign, but in some ways they are like the theoretical musical structures that underlie jazz. They are there to fall back on, and to make you free.

In late 1971, less than a year after Matthiessen started practicing, Love fell ill. After meditating all day on a Saturday, Matthiessen returned home and saw, immediately, in a way that she didn’t yet know herself, that his wife was dying. As he wrote in “The Snow Leopard”: “The certainty of this clairvoyance was so shocking that I had to feign emergency and push rudely into the bathroom, to get hold of myself so that I could speak.” The next day they ended up opposite each other for the daylong meditation, and as they finished a particular chant, Matthiessen had this experience: “The silence swelled with the intake of my breath into a Presence of vast benevolence of which I was a part. . . . I felt ‘good,’ like a ‘good child,’ entirely safe. Wounds, ragged edges, hollow places were all gone, all had been healed; my heart lay at the heart of all Creation. Then I let my breath go, and gave myself up to delighted immersion in this Presence, to a peaceful belonging so overwhelming that tears of relief poured from my eyes.”

Later, Matthiessen’s teacher would confirm that this moment represented an opening for him, a glimpse of

kensho. More important, the clarity achieved would see him through the death of his wife from cancer several months later, helping him find the right words to say in the right moments, without recrimination and self-doubt. It would also lead him to accept an offer, in the wake of Love’s death, to accompany the field biologist George Schaller to the Himalayas as a kind of pilgrimage, which would result in the ecstatic jewel of a book that is “The Snow Leopard.”

As he ascended into the Himalayas, he felt as if he were walking into a myth, up into the mountains and back in time. “If I can’t get a good book out of this,” he remembers thinking to himself, “I ought to be shot.” In the daily journals that comprise the book, he combines penetratingly clear descriptions of the peaks around him with memories of his wife and his pursuit of mystical experience. Somehow — the work of several years of hard editing, among other things — the various strands of Matthiessen’s journey cohere into a kind of fable, in which the potential for clarity and insight struggles to fly free of the past and the people that he (we) can’t ever really let go of. “For fame, for craft, for our enlightenment,” a reviewer wrote in The New York Times when the book was released, Matthiessen and Schaller “did us the old-fashioned honor of risking their lives.”

You might think that winning two National Book Awards for the same book (for “contemporary thought” and nonfiction) would be supremely satisfying, but for Matthiessen, it wasn’t. “ ‘The Snow Leopard,’ he now sees it as a bit of an albatross,” Matthiessen’s third wife, Maria, told me after I visited him in Sagaponack. “People think of him as a nonfiction writer, but he thinks of himself as a fiction writer who wrote these other books.” Asked to “define yourself” — in the first question of the famed “Art of Fiction” interview series in The Paris Review — Matthiessen said: “I am a writer. A fiction writer who also writes nonfiction on behalf of social and environmental causes or journals about expeditions to wild places. . . . I have been a fiction writer from the start. For many years I wrote nothing but fiction.”

“Peter comes from a very distinctive generation of men who take seriously the matter of writing American fiction,” says Elisabeth Sifton, Matthiessen’s editor at Viking Press for “The Snow Leopard” and several other books. “For him, that’s

primum. That’s something I’ve never fully accepted. Because the nonfiction is so stupendous.”

In the late 1960s, The New Yorker sent Matthiessen to Grand Cayman to sail on an old schooner in search of green turtles along the Miskito Bank off Nicaragua. He eventually turned in an article, but he felt that a novel would better express the truth of what he’d seen. He spent the next eight years experimenting with the right way to tell the story, and the book that resulted, “Far Tortuga,” is radical in nearly every way.

Matthiessen uses blank space, pages of dialogue without quotation marks or attribution, pictographs, hand-drawn illustrations and, perhaps most striking for a writer who loves to draw comparisons in his work, only one or two similes in the entire book. “The trouble with metaphors and similes is they bring the author into it,” Matthiessen told me, “and I was trying to stay out of it.” The elimination of the ego is a standard part of Zen training, as is the admonition to keep things simple and free of adornment. “A roach out from underneath the cook shack with its antenna up, that was so striking and strange and beautiful that you don’t need ‘like a radio antenna’ or something like that,” he said. “You just don’t. The thing itself is so good.”

Matthiessen, left, with Taizan Maezumi, center, and Bernie Glassman, at the Zen Community of New York in 1981, rehearsing for Matthiessen's ordination as a Buddhist priest. Credit Peter Cunningham

Robert Stone, writing in The Times, said that “the author’s joy in [the dialect] is so infectious and his ear for it so sure that its music comes to permeate the reader’s consciousness as thoroughly as the wonderful descriptions.” Thomas Pynchon would write, “Matthiessen at his best — a masterfully spun yarn, a little otherworldly, a dreamlike momentum . . . full of music and strong haunting visuals.”

Others hated it. Matthiessen still remembers the review from The Village Voice, “two pages destroying the book, or trying to”; people thought it was too experimental, too difficult, and it never sold as he hoped. Even Matthiessen’s own editor at Random House, Joe Fox — who also edited Truman Capote, Ralph Ellison and John Irving, among others — never fully supported the book. The week before Fox died, in 1995, 20 years after “Far Tortuga” was released, Matthiessen and his wife invited Fox to join them for Thanksgiving dinner. When dinner was over, as Matthiessen was walking Fox out to his car, they got into a heated argument about how Random House had mishandled the book, an argument that continued even after Matthiessen called to apologize once Fox returned home. It was the last conversation the two men would ever have. Even as I sat with him, nearly 40 years after the publication of “Far Tortuga,” the intensity of his feeling was striking. “Those books are so long ago,” I said, in reference to “Far Tortuga” and “The Snow Leopard,” “but they still seem vivid to you now.” Very quietly, very sincerely, he said, “Yes.” When I added that “Far Tortuga” must be a highlight of his career, Matthiessen, for all of the egolessness of the book’s authorial style, was quick to correct me: “Well, no. ‘Far Tortuga’ got no awards,

whatsoever.”

Matthiesen would finally be recognized for his fiction in 2008, with the publication of “Shadow Country,” a sprawling 892-page epic that brought him the National Book Award at the age of 81. The book is a dark mix of many of Matthiessen’s themes — the heedless degradation of the environment and native peoples by modern life and capitalism, the blindness of people to their own behavior and the conflicts that result. As the poet W. S. Merwin noted, “It is the quintessence of his lifelong concerns, and a great legacy.” But you get the sense that the National Book Award, like his father’s eventual begrudging approval after years of estrangement, perhaps came a little too late.

Just off to the side of the main house, at the end of a wooden walk, is an old stable that Matthiessen and several Zen students converted into a

zendo, or meditation hall. Matthiessen has led a small community of Zen practitioners here since 1990, when his American Zen teacher, Bernie Glassman, gave him permission to teach. It’s a humble space, with two rows of black meditation cushions and an altar at one end. On the Saturday of our second interview, I attended morning service in the

zendo with about 15 people who had come from far and near to chant and sit zazen together. After the service ended, one of Matthiessen’s senior students walked me over to the house.

Matthiessen and I sat in his office in the back, talking about “In Paradise,” his new novel. “It was a very odd book and a very difficult book for me to do,” he said. I wondered why, at this stage in his life, he had stuck with it. His legacy is secure, and he has said in numerous places that he thinks most writers don’t know when to quit, that very few do quality work after they get beyond a certain age. “I couldn’t walk away from it,” he said. He stopped for a moment. “It was such a powerful experience, and I just couldn’t walk away from it. I tried.”

The experience was a retreat at Auschwitz in 1996, led by Glassman, who appears in the novel under the transparent designation of “Ben Lama.” The retreatants, who came from all over the globe, sat in meditation on the train platforms in Birkenau where people had been sorted and selected for death. In the evenings, after the sittings, everybody would gather to talk about the day’s experiences. One night, there was a spontaneous outburst of dancing, which was deeply moving for some and outrageous to others. “How does that happen?” Matthiessen asked me rhetorically, posing the question of the novel. He referred back to the novel’s epigraph, a poem by Anna Akhmatova that wonders, when we are surrounded by so much death, “Why then do we not despair?” Matthiessen looked at me, eyes dancing, beating on his leg in time as he said, “Something, something,

something,” unable to name the mysterious life force that allows us to rejoice even at Auschwitz. “That fascinates me.”

On another night during the retreat, Matthiessen stood up to speak. “It was a very charged atmosphere,” Glassman told me, “and he was very passionate when he was talking. He got up and said — I remember so distinctly — that man is basically an evil being.” As Matthiessen remembers it, “I just got up and made a generality that if we think the Germans are unique in this regard, we’re crazy. We’re all capable of this, if the right buttons are pressed. Our countries have all done it. Man has been a murderer forever.” But then he cautioned me to take the drama out of it. “It was no great manifesto up there. I just wanted to say, ‘Come on, we’re all in this together.’ ”

The novel that emerged from Matthiessen’s experiences at Auschwitz is short and stark, narrated by a middle-aged academic named Olin Clements who blunders his way through the entire book. The settings are Krakow and Auschwitz; what little nature there is in the book is bleak, windy and covered in snow. “I felt like I was cold and damp the entire time I was reading the book,” said Becky Saletan, Matthiessen’s editor at Riverhead Books — maybe not the greatest recommendation for the reading experience, yet exactly how Matthiessen wants you to feel. The book is a continuous unresolved argument, between retreatants and inside the mind of the narrator. The few moments of uplift, like the spontaneous outbreak of dancing, are quickly splintered by disagreement.

Olin is not unusual as a fictional character for Matthiessen; many of his subjects are strangers to themselves, acting for reasons they don’t understand, out of some vague impulse to find a “home” that is more an idea than a place they can ever actually return to. In his own life, Matthiessen found a home in Zen. As he writes in “The Snow Leopard”: “In the longing that starts one on the path is a kind of homesickness, and some way, on this journey, I have started home. Homegoing is the purpose of my practice.” And yet, in “In Paradise,” Matthiessen takes even that consolation away. The evil that Olin encounters at Auschwitz is so terrifying that spiritual practice can’t mitigate it. Olin reflects on Solzhenitsyn’s observation that “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being,” and then decides to show it to one of the retreat leaders — who responds with a Buddhist bromide about eliminating “all self-lacerating partial truths while good and evil fall away.” It is correct doctrine, but Matthiessen makes it sound like claptrap. Of spiritual practice in general, with which he has a casual and conflicted relationship, Olin wonders: “How long would such delicate attainments have withstood the death camp’s horrors?” It is another way of asking the question we all ask of ourselves: How would I have fared?

The book is grim, but Matthiessen isn’t. Earlier that morning, I watched as he said goodbye to a guest who stayed over the previous night. They were business associates, friendly but maybe not friends, and as the guest was at the door, he good-naturedly offered optimistic advice about radical experimental measures that Matthiessen might take. Matthiessen smiled and said: “I don’t want to hang on to life quite that hard. It’s part of my Zen training.” In preparing for our interviews, having read “In Paradise,” I wondered whether the Buddhist teachings were providing him any more consolation than they did the characters in his book. I hoped so. “The Buddha says that all suffering comes from clinging,” Matthiessen said. “I don’t want to cling. I’ve had a good life, you know. Lots of adventures. It’s had some dark parts, too, but mainly I’ve had a pretty good run of it, and I don’t want to cling too hard. I have no complaints.”

The characters in “In Paradise” cling too hard and are full of complaints, which is one reason that the book doesn’t feel like any kind of “final word.” The novel lacks the beautiful and affirming moments so much more present in Matthiessen’s nonfiction, moments more beautiful even than the dancing at Auschwitz, because they don’t come with the same complications. When Matthiessen was happy, as a writer and as a traveler, he always let us in on it; most often, he found that happiness in reverence of the natural world and in a hard-won, if fleeting, acceptance of his own uncertain place in it. “Lying back against these ancient rocks of Africa, I am content,” he writes in “The Tree Where Man Was Born.” “The great stillness in these landscapes that once made me restless seeps into me day by day, and with it the unreasonable feeling that I have found what I was searching for without ever having discovered what it was.”

Correction: April 5, 2014 An article on Page 20 this weekend about the writer Peter Matthiessen misstates the nature of the LSD-driven therapy he and his late wife, Deborah Love, took part in. They did it as a couple, not as part of a larger group.

Jeff Himmelman is a contributing writer for the magazine and the author of “Yours in Truth: A Personal Portrait of Ben Bradlee.”