27 May 2014 Last updated at 17:28 - from the BBC

Why is Buddhism so hip? By Dr Andrew Skilton Senior Research Fellow at King's College London

By Dr Andrew Skilton Senior Research Fellow at King's College London

Buddhism has made an indelible mark on popular Western culture. In recent times it has been blessed by celebrity endorsement from the likes of Orlando Bloom, Richard Gere and the retiring rugby union star Jonny Wilkinson, to name just a few.

Indeed Buddhism is now part of the lives of many people with its meditation techniques used in secular settings, from mindfulness courses in the Houses of Parliament to stillness classes in schools.

But what is it about this faith of smiling Buddhas, orange robes and golden temples that has seen it thrive in a Western culture which we are so often told is increasingly secular?

Why do Buddhists meditate?

Buddhism isn't a new addition to our shores. The ancient religion has a long and fascinating history in Britain. The first significant contacts were in the late 19th Century, through colonial officials and missionaries, and pioneering individuals who went east to practise Buddhism there.

It was during the 1960s that the perfect cultural climate for Buddhism in Britain developed. Many Buddhist communities have thrived over succeeding decades and now Buddhism in the UK is represented by a wide variety of traditions, both Asian and home-grown. So how did it take hold in the UK?

Buddhism in bloomBritain emerged shaken, tired and almost bankrupt from World War II. Its empire was collapsing and its economy depressed. We now look back at the 1950s as a rather grim and conformist decade.

By contrast, the '60s are now associated with creativity and non-conformism. The countercultural movement saw an explosion in awareness of Asian religion and cultures. Widespread musical and artistic experimentation; the emergence of 'youth culture' as a powerful economic force; the increasing availability of mind-altering recreational drugs; the collapse of western colonial projects; and the intense controversies around the American Civil Rights movements and the war in Vietnam, all contributed to a profound questioning of received values.

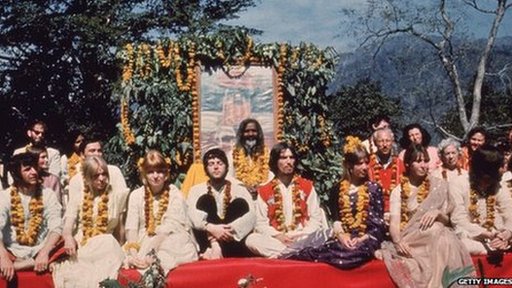

The Beatles in India in with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, 1968

The brief involvement of Mick Jagger and the Beatles in Transcendental Meditation (a Hindu system) was the kind of celebrity endorsement that encouraged an interest in all forms of Asian spirituality. This was enhanced by changing attitudes to authority and a sense of frustration with politics and established religion in the West.

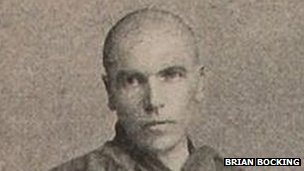

The Irish Buddhist

A feisty working class Irishman named Laurence Carroll became the first known Irish Buddhist monk. Born in Dublin in 1856, he was ordained in Burma and became known as Dhammaloka. He campaigned against the colonial powers on behalf of the Burmese.

A combination of idealistic optimism, full employment, the social confidence nourished by the welfare state, and a rejection of the mind-set behind the Cold War allowed lots of young people to look for something different.

The 1960s saw a flourishing of radicalism, both political, artistic and spiritual. Some people in Britian focussed on Buddhism as a vehicle for newly awakened and adventurous exploration.

Heady stuffCheap international travel and the diaspora of Asian Buddhist teachers in the West enabled people to experiment with practical methods such as meditation and chanting. These practices contrasted with the religious beliefs and rites that many had grown up with, and that could be deemed passive and stuffy by sceptics.

The iconography of Buddhism was strange but enthralling, and Asian Buddhist teachers combined the mystery and excitement of distant cultures with the authority, and promise, of direct experience. For those looking for something different, for freedom from stifling conformity, this was heady stuff.

People come to Buddhism expecting something different. They often have serious spiritual or life questions in mind, but at the same time some are fed up with what they see as conventional religion.

Some of this is about the quest for greener fields, but people also cite patriarchy, fundamentalism, sectarianism and condoning of violence among reasons for their dissatisfaction. Without any knowledge of Buddhist history in Asia, where all these occur, Westerners see Buddhism in a rather idealistic light.

Side-stepping godIn a similar vein, the absence of elaborate hierarchies or involvement in politics makes Buddhism attractive in our egalitarian age. And as established religion has diminished as a source for authoritative guidance about how to live and what to live for, many people have sought fulfilment and understanding in a more personal way from science and the arts.

But neither explicitly have this purpose, and so people seek out a form of spirituality that is compatible with their non-religious beliefs, and once again some find that Buddhism does this well.

In particular, the religions familiar in the West, Christianity, Judaism and Islam, all situate humanity in a finite timeline, running from revelation to an 'end time' - all of which is being managed by God, whereas Buddhism places the human situation in an infinite and neutral cyclical cosmos. Some people find this more compatible with their understanding of the world.

Other people have explicit problems with "God". Buddhism side steps God and offers a vision of humanity and the spiritual life that is not dependent on a deity. It lays out a path of self-transformation, and people like the idea of being in control and taking responsibility for their lives that can come with this.

Buddhism in Scotland

The arrival of Tibetan teachers Chogyam Trungpa and Akong Rinpoche, fleeing the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1959, led to the setting up of a permanent meditation centre, Samye Ling, in Eskdalemuir in the 1960s.

In turn this resonates with the broader therapeutic and self-help culture that has evolved in the West out of psycho-analysis and psychiatry. Buddhism has a lot to say about the mind and so seems to sit well alongside contemporary "mind sciences" as we acknowledge the importance of mental states in all aspects of our lives - from work to family life, from sport to spirituality.

And international travel still plays a role. Many people have now holidayed in Buddhist countries and come away with a liking for Buddhists and the type of culture that Buddhism nourishes.

Looked at another way, Buddhism offers seemingly practical ways of developing wisdom and compassion, free from guilt and obligation. And of course, I think there is the simplest explanation of all for why Buddhism is hip, which is that it offers something that is helpful and meaningful, and that people just like it for what it is in itself.