| OBC Connect

A site for those with an interest in the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives, past or present, and related subjects.

|

| | | China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos |  |

| | | Author | Message |

|---|

Jcbaran

Posts : 1620

Join date : 2010-11-13

Age : 73

Location : New York, NY

|  Subject: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos Subject: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos  5/4/2014, 10:52 am 5/4/2014, 10:52 am | |

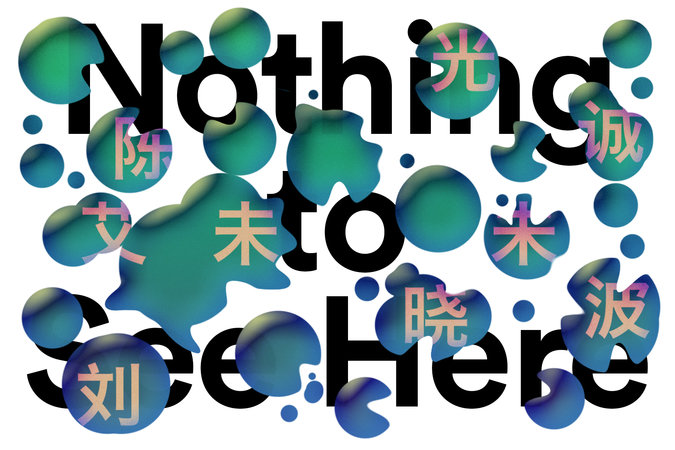

| China’s Censored WorldBy EVAN OSNOS MAY 2, 2014  In February, while I finished work on a book about China, a publishing company in Shanghai asked for an early copy, in order to begin a translation. The book follows people I’ve come to know, some prominent, others not, as they try to change their lives in a country throbbing with possibility — individuals like Gong Haiyan, a farmer’s daughter and businesswoman who envisions herself in a “race against the clock, to seize the initiative before it’s lost.” After reading the manuscript, an editor in Shanghai replied with enthusiasm, but also sent me a list of politically active people in the narrative who, he wrote, “would be difficult” to include in the Chinese edition: a lawyer (Chen Guangcheng), an artist (Ai Weiwei), three writers (Liu Xiaobo, Murong Xuecun, Han Han) and “a few others.” He made a proposal: “Please kindly let me know if it is possible for us to cooperate on a special version of your book for its Chinese publication.” I had a choice to make. The defining fact of China in our time is its contradictions: The world’s largest buyer of BMW, Jaguar and Land Rover vehicles is ruled by a Communist Party that has tried to banish the word “luxury” from advertisements. It is home to two of the world’s most highly valued Internet companies (Tencent and Baidu), as well as history’s most sophisticated effort to censor human expression. China is both the world’s newest superpower and its largest authoritarian state. For most of Chinese history, readers had limited access to books from abroad. In the 1960s and ’70s, when foreign literature was officially restricted to party elites, students circulated handwritten, string-bound copies of J.D. Salinger, Arthur Conan Doyle and many others. But in the past three decades, rules have relaxed somewhat and sales of foreign writers have ballooned, thanks to Chinese consumers who are ravenous for new information about themselves and the world. In 2012, the most recent year for which statistics are available, China’s 580 state-owned publishers acquired the rights to more than 16,000 foreign titles, up nearly tenfold since 1995; current hot sellers range from Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” to Henry A. Kissinger’s “On China.” Ever since the reign of the first emperor, who oversaw the burning of Confucian texts in 213 B.C., Chinese leaders have valued the science of censorship. To release a book in China today, foreign authors must accept the judgment of a publisher’s in-house censors, who identify names, terms and historical events that the party considers unflattering or a threat to political stability. When the Chinese edition of Khaled Hosseini’s novel “The Kite Runner” was published in 2006, critical references to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan were removed. (For Chinese authors, the stakes are incomparably larger; they either heed restrictions or lose the ability to publish in their home country. Prosecutors can cite published writing as evidence of “incitement to subvert state power.”) If publishers overlook a taboo, the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television can pull books from the shelves and punish those responsible. Similar scrutiny applies to television shows, films and radio programs, and the government keeps an especially close eye on broadcasting, because it reaches the most people. When President Obama, in his first inaugural address, mentioned earlier generations who “faced down fascism and Communism,” China’s state broadcaster cut away. The word “Communism” did not appear on transcripts published in the Chinese press. Living and writing in Beijing from 2005 to 2013, I found that the precise boundaries of the censored world were difficult to map. Though some rules leak to the public — last month, the State Council Information Office advised all websites to “find and remove the video titled ‘Actual Footage of Chengdu Police Surrounding and Beating Homeowners Who Were Defending Their Rights”’ — most of the censored world is populated by unmentionable names and untellable stories, defined by rules that are themselves secret. The Central Propaganda Department, the highest-ranking agency responsible for “thought work,” does not report on its activities; it is so averse to attention that its headquarters, on the Avenue of Eternal Peace, have no address or sign. To quantify one realm of Chinese censorship, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, in 2012, studied messages on Sina Weibo, the social media site. They found that more than 16 percent of all posts were deleted because of the content. One known fact about China’s censored world is that it is growing. Movie theaters are proliferating by the day, and Hollywood makes the cuts required to reach them. The makers of “Skyfall,” the latest James Bond film, removed a scene involving the killing of a Chinese security guard, and a plot line in which Javier Bardem says he became a villain during his time in Chinese custody. The New York Times has been unable to receive new residency visas for journalists for more than a year, because it reported on the family wealth of Chinese leaders. Bloomberg News is facing similar retaliation for its investigations of party officials. In March, the Bloomberg L.P. chairman, Peter T. Grauer, said the company “should have rethought” the decision to range beyond business news, because it jeopardized the company’s potential market in China. But as I considered publishing a book in China, local publishers gradually filled in a road map of the censored world. On behalf of a company in Beijing, an agent wrote, “To allow the publication in China, the author will agree to revise nearly 1/4 of the contents.” The publisher had itemized trouble spots chapter by chapter, beginning with a line in the prologue: “China has never been more pluralistic, urban, and prosperous, yet it is the only country in the world with a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in prison.” (The first half of the sentence could stay.) Some taboos were foreseeable; the publisher worried about a mention of Mao’s Great Leap Forward, because that project resulted in a famine that killed between 30 and 45 million people. Other problems were subtler; since the party credits its economic success to Deng Xiaoping, I was advised not to lavish too much praise on the contributions of his peers. Judging by the notes, the censor seemed to grow exasperated: “Chapter 14: The whole chapter is about Chen Guangcheng.” (I write about Mr. Chen, a blind lawyer now in exile in the United States, as an example of Chinese determination to defy the circumstances of birth.) In some cases, the censors’ requirements startled me: The former politician Bo Xilai, a one-time rising star now serving a life sentence for corruption, was convicted in a trial covered by state television, so why is discussion of him sensitive? The problem, it seemed, is how it can be mentioned, and how much. When an official version of history has been written, an unofficial version becomes unwelcome. A foreign author who wants to publish in China can find many reasons to tolerate the demands for censorship. A book, even compromised, might inspire a new generation of readers to demand information from beyond their borders; it might help pay for the writing of the next book (or, let’s face it, a new roof). As a writer, it is tempting to rationalize the discomfort by emphasizing the percentage of the book that survives the cuts, rather than the percentage that is censored. But those explanations fail to surmount an inexorable problem. The most difficult part of writing about contemporary China is capturing its proportions: How much of the story is truly inspiring, and how much of it is truly grim? How much of its values are reflected in technology start-ups and stories of self-creation, and how much of its values are reflected in the Great Firewall and abuses of power? It is tempting to accept censorship as a matter of the margins — a pruning that leaves the core of the story intact — but altering the proportions of a portrait of China gives a false reflection of how China appears to the world at a moment when it is making fundamental choices about what kind of country it will become. In the end, I decided not to publish my book in mainland China. (It will be available to Chinese readers from a publisher in Taiwan.) To produce a “special version” that plays down dissent, trims the Great Leap Forward, and recites the official history of Bo Xilai’s corruption would not help Chinese readers. On the contrary, it would endorse a false image of the past and present. As a writer, my side of the bargain is to give the truest story I can. Evan Osnos, a staff writer at The New Yorker, is the author of “Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China.” | |

|   | | Jcbaran

Posts : 1620

Join date : 2010-11-13

Age : 73

Location : New York, NY

|  Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos  5/4/2014, 11:30 am 5/4/2014, 11:30 am | |

| China has been "censoring" or controlling religious, culture and political expression and history for over 2,000 years. There is nothing new here. Censoring is probably not the right word. It is thought control and myth making, constantly establishing and reinforcing the ONE master narrative or root paradigm - and there is only ONE way to look at any particular aspect of life - and to question it or vary from it would result in banishment, imprisonment or death.

It was not that much different in Japan, but China took the myth-making so seriously, it had an established significant class of literati / scholars / scribes - whose only job was to fabricate tales of the eminent monks and sages - and these became the official "histories" when in fact, they were mostly or entirely myth. The persons may have been real monks, but most or all the details of their lives and teachings were written following a standardized pattern - and the scholars did not care how "true" they were. Truth had nothing to do with this process. It was to create and promulgate the concept of the IDEAL MONK and the ideal religion that supported the emperor and the state and the society - and anything else was irrelevant. These tales held no shadows or controversies, and they are interesting not because they might contain a smidgen of historic fact, but how the tales expressed the political and social and spiritual needs and values of when they were actually written - and then re-written.

Rinzai's words - yes, there was a monk named Linchi, but all of what is attributed to him, most likely gathered from all kinds of sources over 150 years after he died. He might not have said any of it, but he became this huge figure based on the hagiography / the myth. Hui-Neng - as we discussed elsewhere - there was an obscure monk with that name, but as "the Sixth Patriarch" - no, that's a story. And the grand story of the unbroken lineage back to the Buddha itself, myth making, good marketing. But once these mega narratives were established and accepted by the ruling class, the emperor, these core tales became absolute dogma, unquestioned. And the imperial system rigidly controlled all aspects of religion - including what scriptures could be read, the different schools or practices, ordination, the official temples, the abbots of the temples. no freedom of religion or thought or practice.

The only exception to this may have been at the periphery of the empire - where the renegades or misfits could go and set up their own quiet / hidden scenes, as far away from political power as possible, but even those monks and communities would eventually come under the control of local governors.

So all the stories of the great Chan masters from Tang and Song China that have come down through the various "Transmission of the Lamp" collections - were cobbled together, based on snippets of history, but mostly written to suit the needs of the time and are not history, not biography. Even with all those specific details - that was part of the process. To make them more credible, the scholars went to great lengths fabricating specific facts and stories - in fact, the more detail, the more certain you can be that the biography is nearly entirely myth. The ideal was everything. The root paradigm / the master narrative was the point. "Truth" irrelevant.

At the same time, yes, many of the teachings and insights contained in these collections were and still are profound - wherever they came from, whoever said them. So, from that point of view, I think they are of great value. But not as history - and they still need to be read critically - at least that's my take on this. Even many of the teachings were changed over the years to fit the current trend or point of view or to please the current imperial court. When Chan became dominant in the Song period, there were new collections of biographies that contained the newer Chan approach, more wild, more iconoclastic - but also edited to please the current fashion.

Always ONE VERSION / ONE NARRATIVE allowed.

In two millennia, not much has changed. What is it about China that this mindset is so strong? It can't be in the people's DNA. But it clearly has deep roots. Many people thought that as the internet became more pervasive and China's economy grew, naturally, inexorably freedom of expression, the press would come. There are many political and economic writers who predicted this. But no. China just expanded their control - and now we hear that there are something like 500,000 people whose job it is to monitor, censor and control information, the internet, all forms of communication. One master narrative. | |

|   | | david.

Posts : 124

Join date : 2012-07-29

|  Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos  5/5/2014, 3:39 am 5/5/2014, 3:39 am | |

| Hi Josh.

Thank you for keeping posting all the stuff you do.

I am still taking in the historical lies of Zen. It still amazes me that the lineage i chanted at throssel daily was a lie. The trouble for me as i learn more, is if that was a lie and that was a lie and that was a lie, what isnt a lie? and if the transmission is a lie, there are no authorative teachers... so why are they all pretending to be? isn't pretending the opposite of truth?

Zen Transmission as of today:

Some guy says you've got "there".....

and he "knows" cos some alcoholic or abuser says he got "there".....

And that alcoholic or abuser "knows" cos he left the far east for dubious reasons....

And they all say you can't say you're "there" unless someone who says he's "there" tells you you are...

and they are beginning to say this system is flawed, we need a committee of "there" people decide that you are "there".

For ++++'s sake people...... | |

|   | | Isan

Admin

Posts : 933

Join date : 2010-07-27

Location : California

|  Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos  5/5/2014, 9:52 am 5/5/2014, 9:52 am | |

| - david. wrote:

I am still taking in the historical lies of Zen. It still amazes me that the lineage i chanted at throssel daily was a lie. The trouble for me as i learn more, is if that was a lie and that was a lie and that was a lie, what isnt a lie? and if the transmission is a lie, there are no authorative teachers... so why are they all pretending to be? isn't pretending the opposite of truth? It's understandable that you feel you were lied to if you believed that the lineage was historically true and that was important to you. Unfortunately you did not have the benefit of being told that the Buddhas preceding Shakyamuni were not historic Buddhas. They were there to indicate that the truth appears in the world without relying on lineage or any other human device or contrivance. Jiyu Kennett made reference to this on occasion and also said that the whole edifice of Zen practice was delusion added to delusion to (hopefully) facilitate learning. I was disillusioned when I left Shasta Abbey but not in Buddhism. Shakyamuni was also disillusioned by the teachers he studied with. When asked what Zen was one teacher answered "going from one mistake to the next" (I wish I could remember who that was). Transmission is not a lie. People make mistakes, things go wrong, life goes on. | |

|   | | david.

Posts : 124

Join date : 2012-07-29

|  Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos  5/10/2014, 9:16 am 5/10/2014, 9:16 am | |

| Hi Isan. I have read a lot of what Josh has posted on transmission, and other stuff on the web about the old and recent history of Buddhism. What isn't a lie about historical Buddhist transmission?

And as for present day transmission, of any person to person type whatsoever, who is the Buddhist authority you can trust today to transmit to you?

Transmission is, I am finding out, just a mental construct. and like all mental constructs, something of no importance when I reside in the unconditioned. and it certainly was of no help in me letting go into the unconditioned. | |

|   | | Isan

Admin

Posts : 933

Join date : 2010-07-27

Location : California

|  Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos  5/10/2014, 9:33 am 5/10/2014, 9:33 am | |

| - david. wrote:

- Hi Isan. I have read a lot of what Josh has posted on transmission, and other stuff on the web about the old and recent history of Buddhism. What isn't a lie about historical Buddhist transmission?

And as for present day transmission, of any person to person type whatsoever, who is the Buddhist authority you can trust today to transmit to you?

Transmission is, I am finding out, just a mental construct. and like all mental constructs, something of no importance when I reside in the unconditioned. and it certainly was of no help in me letting go into the unconditioned. My personal opinion, which is based on my experience and has nothing to do with the history of use and abuse of Transmission in Buddhism, is that Transmission is simply one person who has experienced IT telling another person who has experienced IT "Yes, that's IT". We all need (or at least benefit from) validation from time to time. The story goes that Shayamuni held up a flower for Makakasho. Like most Zen stories this has been analyzed to death, but it very likely was just the teacher's way of telling the student that they were on the same page. It doesn't have to turn into a big magical mystery tour. It seems to me that you went to Daishin Morgan because you needed the same, and when you didn't get it from him you went to someone else and got it there instead - end of story. | |

|   | | david.

Posts : 124

Join date : 2012-07-29

|  Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos  5/10/2014, 9:49 am 5/10/2014, 9:49 am | |

| Hi Isan.

The Makakasho flower story, it seems, is a lie invented in the 11th Century by some lier. The Buddha, it seems, denied any transmission....

Anando didnt spend much time with me. I felt no transmission. He was nice though. Interestingly a year or so later it was revealed he had serious issues talking to half the world's population. He left his order under a cloud, married a Medium, then died a year later of a brain tumour. So what exactly do you know about that he transmitted to me. I felt no transmission and I was there... | |

|   | | maisie field

Posts : 77

Join date : 2012-08-13

|  Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos  5/12/2014, 12:33 pm 5/12/2014, 12:33 pm | |

| So there isn't anyone who has more authority then you, about the experiences you have had!

Fantastic! You are the authority!

I am the authority!

Sounds ok .....

Isn't it ? | |

|   | | Sponsored content

|  Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos Subject: Re: China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos  | |

| |

|   | | | | China's Censored World - from the NYT by Evan Osnos |  |

|

Similar topics |  |

|

| | Permissions in this forum: | You cannot reply to topics in this forum

| |

| |

| |

|