7 Lessons (Some Embarrassing) I Learned After Writing A Book About MeditationBy Dan Harris - January 5, 2015 6:00 AM EST

In 2014, to my vast surprise, I became a public evangelist for meditation. I published a memoir called

10% Happier, about an ambitious, agnostic anchorman who reluctantly embraces mindfulness meditation after a drug problem, an on-air freak-out, and an unplanned "spiritual" journey.

I wrote the book in order to convince fellow skeptics that meditation is not, despite its PR problem, only for people who wear patchouli and use the word "Namaste" un-ironically. In the nine months since the book came out, I have learned some valuable lessons, many of which involved having my own advice shoved back into my face.

I list them here because if you're thinking about setting meditation as a new year's resolution, you might find some of these lessons useful, or at the very least amusing.

1. Don't forget the basics.

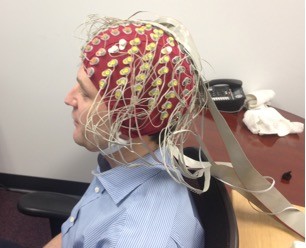

This is a picture of me having my meditation skills tested by neuroscientists. I didn't do so well. Every time I was supposed to be shutting down the so-called, Default Mode Network of my brain — the regions that fire up when we're thinking about ourselves, ruminating about the past or projecting into the future — I was achieving just the opposite. My DMN was lit up like a Christmas tree.

After doing scores of TV appearances, radio interviews and speeches in which I lectured people about the value of meditation, it turns out I had forgotten the most basic instructions. The whole game is to try to focus on your breath and then when you get lost, to gently start again. And again. And again …

Instead, I was getting all overheated and self-lacerating about the inevitable wanderings of my mind.

In my defense, it's hard to relax when you're wearing a stupid-looking skullcap, and being scrutinized by a team of researchers. But still, it was an important reminder. As my friend and meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg later advised me, when it comes to meditating, "It helps to have a sense of humor."

2. Science is the gateway, not the path.

In making the case for meditation, I rely heavily on the explosion of scientific research that — while still in its infancy — strongly suggests a long list of tantalizing health benefits. Studies have shown meditation can do everything from lowering your blood pressure to boosting your immune system, to literally rewiring key parts of your brain for happiness.

However, I've come to see that while science is a great tool for roping in those who might otherwise reflexively reject meditation as New Age poppycock, it only goes so far. People may

start meditating because of the science, but nobody

continues to meditate because they think their prefrontal cortex is changing; they keep doing it because they find themselves calmer, more focused and less yanked around by their emotions.

3. Proselytize with care — or, better yet, not at all.While I have no compunction about preaching the benefits of meditation in front of large groups, I try never to do it one-on-one. For example, my wife still does not meditate consistently (even though she really appreciates the fact that the practice has made her husband less of a [banned term]). Whenever I'm tempted to urge her — or anyone, really — to meditate, I try to bear in mind a recent cartoon from

The New Yorker, which features two women ordering lunch at a restaurant. One of them says to the other, "I've only been gluten-free for a week, but I'm already really annoying."

4. Happiness is not complacency.

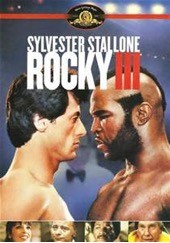

A few weeks after my book came out, I was invited to do an interview at the last place on Earth I thought I'd ever talk meditation: Fox News. The anchor asked me a great question — something along the lines of, "If I get too happy, won't I end up like Rocky from Rocky III?"

For those of you who haven't seen this Sly Stallone classic in a while, it opens with a montage of the boxer, fresh off of winning the championship, signing autographs, shooting TV commercials, and gamboling around his mansion with his wife and son. These scenes are intercut with images of a vaguely psychopathic-looking Clubber Lang (played by Mr. T) training hard and drubbing his opponents. By the second round of their fight, Rocky is on the mat, bleeding and unconscious.

The Fox News guy was worried that meditation would leave him vulnerable to leaner, hungrier opponents. But this is to confuse happiness with complacency. The proposition of meditation, at least as I understand it, is not that you should abandon stress. A certain amount of plotting and planning is inherent in striving for greatness in any arena — from your career to volunteer work, to parenting and art.

But we tend to make our stress worse than it needs to be. As I like to say, meditation helps you draw the line between "constructive anguish" and useless rumination. That, my friends, is a game-changer.

5. Meditation is more than self-improvement.

I made this argument in my book, but I feel even more strongly about it now. All the hard work and mind-wrangling of meditation (the image above was briefly considered as the cover art for my book) is not just to make you better at your job; it should also make you a nicer person — which, by the way, can also make you more successful.

Let me unpack this. Of late, there has been something of a backlash in Buddhist circles to the mainstreaming of meditation. Critics call it "McMindfulness." One of the gripes is that selling meditation as a way to make more effective soldiers and corporate samurai, denudes the practice of one of its central components: compassion.

Despite the fact that I am a vocal cheerleader for mainstreaming, I happen to agree with the critics on this point. But here's the thing: it's possible to make the case for compassion in a way that appeals to self-interest, as opposed to finger wagging and moralizing.

Studies have shown that compassionate people are healthier, more popular and more successful. Moreover, there's research that suggests a meditation can actually

make you nicer. This is the ground upon which the mainstreamers and the McMindfulness critics can and should meet. As I call it in

10% Happier, it's the "self-interested case for not being a [banned term]."

6. It's not about you.

The events of the past year have been amazing. Beyond amazing. I've been given the chance to talk meditation on

Colbert, at Google, and to a gaggle of billionaires in Aspen. I've also been invited to speak to social workers, cancer survivors and inner-city high school students. You might think this kind of run would be an egotistic

rumspringa. And while it has, of course, been validating, it's also been truly humbling.

To be clear, I usually get suspicious when people use that word — humbling. When Hollywood types get up to accept an Academy Award and prattle on about how "humbled" they are, it never fails to set off my [banned term] meter.

By contrast, what happened to me was, I would argue, genuinely so.

Actually, at first, it was mostly just terrifying. In the book I reveal that, after covering wars for ABC News, I'd gotten depressed, and then self-medicated with recreational drugs — all of which culminated in a panic attack, live on

Good Morning America.

I worried that telling this story might derail my career. However, when I finally shared the secrets that I'd been hiding for a decade, I came to the following realization: people don't really care that much about me. We're all the stars of our own movie. These personal details that I thought were so heavy were, in the end, just mildly titillating to the rest of the world.

What people really wanted to know was: "What do you have for me, Harris?" And on that score, I feel increasingly confident. The more I travel around and talk about meditation, the more convinced I am that this is something truly and universally useful.

7. 10% is an understatement.

When I came up for the title of my book, I knew it was an absurdly unscientific estimate. But I liked it because it's true enough — and it also sounds like a good return on investment. However, the more I meditate, the more I've come to believe that the 10% compounds annually.

I'm clearly pulling this out of my rear end, but bear with me. The graph to the left (which I drew) describes how I think this works.

Psychologists believe we all have a "happiness set point." When good things happen, our happiness spikes; when bad things happen, our happiness dips.

But overall, we tend to gravitate back to our set point. In my view, meditation makes the good stuff better, because we are able to be awake and present enough to enjoy it. And it makes the bad stuff less bad, because we have learned how to cut short the useless rumination.

Meanwhile, meditation raises our set point to an entirely new level. Again, I'm just making this [banned term] up — but it certainly feels true for me, and for the people I know who meditate.

In closing, one final, personal note:

On December 15, 2014, I got a major dose of the "good stuff" when this little dude came into my life:

Meet Alexander Robert Harris, our new baby boy.

After he was born, a colleague of mine from ABC News sent me this revised book cover, which pretty much says it all.

Images courtesy of the author