| OBC Connect

A site for those with an interest in the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives, past or present, and related subjects.

|

|

| | Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D. T. Suzuki |  |

| | | Author | Message |

|---|

Jcbaran

Posts : 1620

Join date : 2010-11-13

Age : 74

Location : New York, NY

|  Subject: Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D. T. Suzuki Subject: Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D. T. Suzuki  8/5/2013, 4:45 pm 8/5/2013, 4:45 pm | |

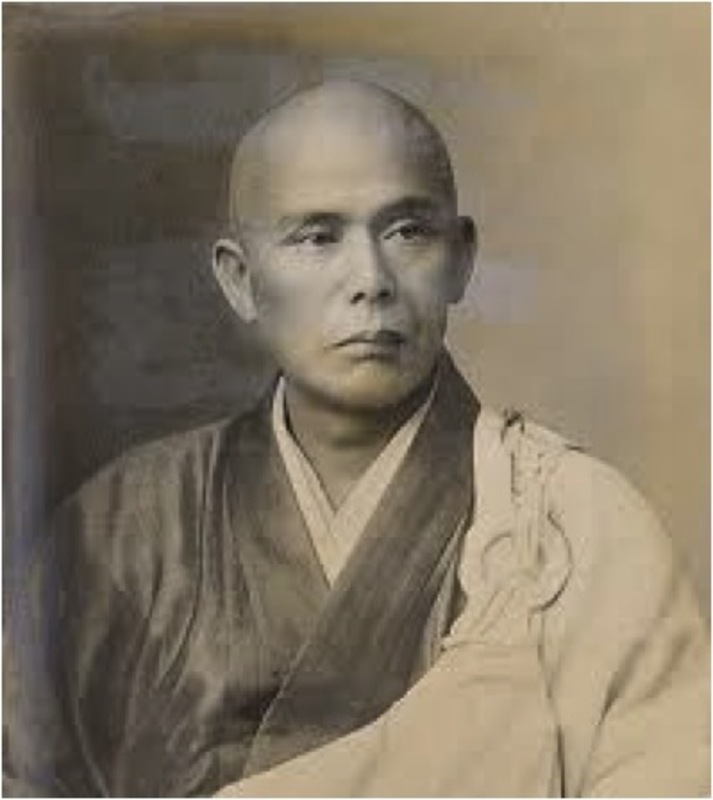

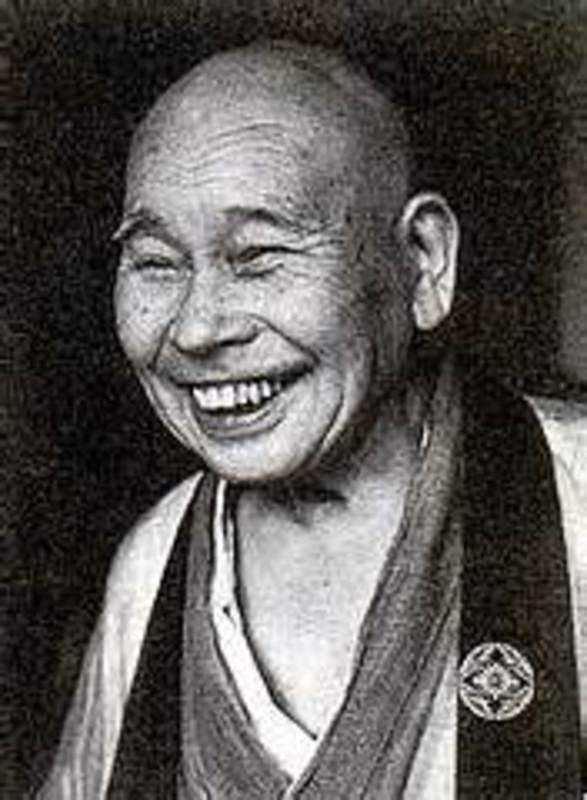

| The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 30, No. 4, August 5, 2013Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D.T. SuzukiBrian Daizen VictoriaIntroductionThe publication of Zen at War in 1997 and, to a lesser extent, Zen War Stories in 2003 sent shock waves through Zen Buddhist circles not only in Japan, but also in the U.S. and Europe. These books revealed that many leading Zen masters and scholars, some of whom became well known in the West in the postwar era, had been vehement if not fanatical supporters of Japanese militarism. In the aftermath of these revelations, a number of branches of the Zen school, including the Myōshinji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect, acknowledged their war responsibility. A proclamation issued on 27 September 2001 by the Myōshinji General Assembly included the following passage: As we reflect on the recent events [of 11 September 2001] in the U.S. we recognize that in the past our country engaged in hostilities, calling it a “holy war,” and inflicting great pain and damage in various countries. Even though it was national policy at the time, it is truly regrettable that our sect, in the midst of wartime passions, was unable to maintain a resolute anti-war stance and ended up cooperating with the war effort. In light of this we wish to confess our past transgressions and critically reflect on our conduct. 1On 19 October 2001 the sect’s branch administrators issued a follow-up statement: It was the publication of the book Zen to Sensō [i.e., the Japanese edition of Zen at War], etc. that provided the opportunity for us to address the issue of our war responsibility. It is truly a matter of regret that our sect has for so long been unable to seriously grapple with this issue. Still, due to the General Assembly’s adoption of its recent “Proclamation” we have been able to take the first step in addressing this issue. This is a very significant development. 2In the same year, the smaller Tenryūji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect issued a similar statement, again citing the Japanese edition of Zen at War as a catalyst leading to their belated recognition of war responsibility. In reading these apologies, one is reminded of the “Stuttgart Confession of Religious Guilt,” issued by Protestant church leaders in postwar Germany, in which they repented their support of Hitler and the Nazis. The Confession’s second paragraph read in part: “With great anguish we state: Through us has endless suffering been brought upon many peoples and countries. . . . We accuse ourselves for not witnessing more courageously, for not praying more faithfully, for not believing more joyously, and for not loving more ardently.” 3 Nevertheless, there is one significant difference between religious leaders in Japan and Germany, i.e., while the Stuttgart Confession was also issued on 19 October, it was 19 October 1945 not 2001. It is also true that a relatively small number of German Christians resisted the Nazis, Father Maximillian Kolbe, Martin Niemöller and Dietrich Bonhoeffer being among the best known. Similarly a small number of Buddhist priests, both within the Zen school and other sects, also opposed Japanese imperialism. The common denominator between the two groups, however, was their overall ineffectiveness. 4 This is no doubt because no matter what the faith or country involved, institutional religion, with but few exceptions, staunchly supports its own nation in wartime. The Background to D.T. Suzuki’s Wartime Role There is now near universal recognition, including in Japan, that the Zen school, both Rinzai and Sōtō, strongly supported Japanese imperialism. Nevertheless, there is one Zen figure whose relationship to wartime Japan remains a subject of ongoing, sometimes deeply emotional, controversy: Daisetz Teitarō Suzuki, better known as D.T. Suzuki (1870-1966). 5

D.T. Suzuki |

Given Suzuki’s position as the most important figure in the introduction of Zen to the West, it is hardly surprising that the nature of his relationship to Japanese imperialism should prove controversial, for if he, too, were an imperialist supporter, what would this imply about the nature of the Zen he introduced to the West? If the following discussion of Suzuki’s wartime record appears to lack balance, or shades of gray, it is not done out of ignorance, let alone denial, of exculpatory evidence concerning this period in his life. However, evidence of Suzuki’s alleged anti-war stance is well known and, indeed, readily accessible on the Internet. 6 Hence, there is no need to repeat it here. That said, interested readers are encouraged to review all relevant materials related to Suzuki’s wartime record before reaching their own conclusions. As important as Suzuki may be, the debate goes far beyond either the record or reputation of a single man. As recent scholarship suggests, Suzuki was in fact no more than one part, albeit a significant part, of a much larger movement. Oleg Benesch described Suzuki’s role as follows: - Quote :

- [Suzuki’s] writings on bushidō and Zen during the period immediately after the Russo-Japanese War [1904-05] are not extensive, but are significant in light of his role in spreading the concept of the connection of Zen and bushidō, especially during the last four decades of his life. Suzuki can be seen as the most significant figure in this context, especially with regard to the dissemination of a Zen-based bushidō outside of Japan.7 (Italics mine)

While these comments may not seem particularly controversial, Benesch also provided a detailed history of the manner in which Suzuki and other early twentieth century Japanese intellectuals, including such luminaries as Nitobe Inazō (1862-1933) and Inoue Tetsujirō (1855-1944), essentially invented a unified bushidō tradition for nationalist use both at home and abroad. Benesch writes: - Quote :

- The development and dissemination of bushidō from the 1880s onward was an organic process initiated by a diverse group of thinkers who were more strongly influenced by the dominant Zeitgeist and Japan’s changing geopolitical position than by any traditional moral code. These individuals were concerned less with Japan’s past than the nation’s future, and their interest in bushidō was prompted primarily by their considerable exposure to the West, pronounced shifts in the popular perception of China, and an apprehensiveness regarding Japan’s relative strength among nations.8

Benesch later added: - Quote :

- The bushidō that developed in Meiji [1868-1912] was not a continuation of any earlier ethic, but it contained factual elements that were carefully selected and reinterpreted by its promoters. . . .concepts such as loyalty, self-sacrifice, duty, and honor, all of which existed in considerably different forms and contexts to those in which they were incorporated into modern bushidō theories. . . .The most important factor in the relatively rapid dissemination of bushidō was the growth of nationalistic sentiments around the time of the Sino-Japanese [1894-95] and Russo-Japanese wars.9

As this article reveals, Suzuki’s writings on the newly created bushidō ‘code’ were very much a part of this larger nationalist discourse. His personal contribution to this discourse was the presentation of bushidō, primarily to a Western audience, as the very embodiment of Zen, including the modern Japanese soldier’s alleged “joyfulness of heart at the time of death.” In 1906, the year following Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War, Suzuki wrote: - Quote :

- The Lebensanschauung of Bushidō is no more nor less than that of Zen. The calmness and even joyfulness of heart at the moment of death which is conspicuously observable in the Japanese, the intrepidity which is generally shown by the Japanese soldiers in the face of an overwhelming enemy; and the fairness of play to an opponent, so strongly taught by Bushidō – all of these come from the spirit of the Zen training, and not from any such blind, fatalistic conception as is sometimes thought to be a trait peculiar to Orientals.10

Suzuki’s praise for, and defense of, Japan’s soldiers as “Orientals” is particularly noteworthy in light of the fact that only two years earlier, i.e., in 1904, Suzuki had himself invoked Buddhism in attempting to convince Japanese youth to die willingly for their country: “Let us then shuffle off this mortal coil whenever it becomes necessary, and not raise a grunting voice against the fates . . . . Resting in this conviction, Buddhists carry the banner of Dharma over the dead and dying until they gain final victory.” 11While comments like these may be interpreted as Suzuki’s ad hoc responses to national events beyond his control, in fact they accurately represent his underlying belief in the appropriate role of religion in a Japan at war. This is clearly demonstrated by the following comments in the very first book Suzuki published in November 1896, entitled A Treatise on the New Meaning of Religion ( Shin Shūkyō-ron): - Quote :

- At the time of the commencement of hostilities with a foreign country, marines fight on the sea and soldiers fight in the fields, swords flashing and cannon smoke belching, moving this way and that. In so doing, our soldiers regard their own lives as being as light as goose feathers while their devotion to duty is as heavy as Mount Tai [in China]. Should they fall on the battlefield they have no regrets. This is what is called “religion during a [national] emergency.”12

The year 1896 is significant for two reasons, the first of which is that Suzuki’s book appeared in the immediate aftermath of Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese War. This was not only Japan’s first major war abroad but, with the resultant acquisition of Taiwan, marked a major milestone in the growth of Japanese imperialism. Thus, Suzuki’s call for Japan’s religionists to resolutely support the state whenever it went to war could not have been more timely. At a personal level, it was also in December of that year, i.e., just one month after his book appeared, that Suzuki had his initial enlightenment experience ( kenshō). This occurred at the time of his participation as a layman in an intensive meditation retreat ( sesshin) at Engakuji in Kamakura, and shortly before his departure for more than a decade-long period of study and writing in the U.S. (1897-1908).

Engakuji |

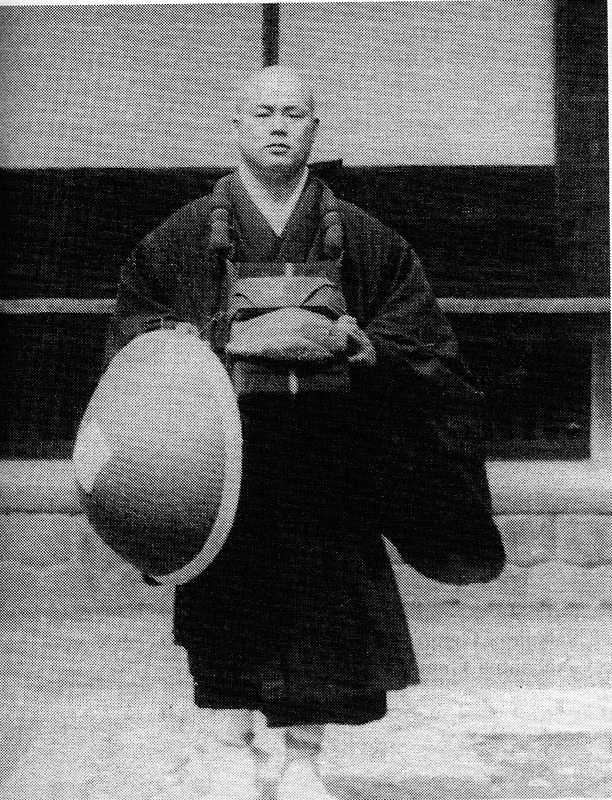

As Suzuki’s subsequent statements make clear, his kenshō experience did not alter his view of “religion during a [national] emergency.” Again, this is hardly surprising in light of the fact that Suzuki’s own Rinzai Zen master, Shaku Sōen [1860-1919], Engakuji’s abbot, was also a strong supporter of Japan’s war efforts.

Shaku Sōen |

In fact, Shaku’s support of Japan was so strong that during the Russo-Japanese War he volunteered to go to the battlefields in Manchuria as a military chaplain. Shaku explained: “. . . I also wished to inspire, if I could, our valiant soldiers with the ennobling thoughts of the Buddha, so as to enable them to die on the battlefield with the confidence that the task in which they are engaged is great and noble.” 13Once Japan had defeated Russia, its imperial rival, it immediately forced Korea to become a Japanese protectorate in November 1905. This was followed by Japan’s complete annexation of Korea in August 1910, thereby cementing the expansion of the Japanese empire onto the Asian continent. For his part, Suzuki avidly supported Japan’s takeover of Korea as revealed by comments he made in 1912 about that “poor country,” i.e., Korea, as he traversed it on his way to Europe via the Trans-Siberian railroad: - Quote :

- They [Koreans] don’t know how fortunate they are to have been returned to the hands of the Japanese government. It’s all well and good to talk independence and the like, but it’s useless for them to call for independence when they lack the capability and vitality to stand on their own. Looked at from the point of view of someone like myself who is just passing through, I think Korea ought to count the day that it was annexed to Japan as the day of its revival.14

Suzuki’s comments reveal not only his support for Japanese colonialism but also his dismissal of the Korean people’s deep desire for independence. For Suzuki, the future of a poverty-stricken Korea depended on Japanese colonial beneficence. While no doubt many if not most of Suzuki’s countrymen would have agreed with his position at the time, readers of Zen at War will recognize in both Suzuki and Shaku’s comments early examples of the jingoism that characterized Zen leaders’ war-related pronouncements through the end of the Asia-Pacific War in 1945. Not only did Suzuki admonish Buddhist soldiers to “carry the banner of Dharma over the dead and dying,” they were also directed “not to raise a grunting voice against the fates” as they “shuffle off this mortal coil.” In point of fact, approximately 47,000 young Japanese laid down their lives in the Russo-Japanese War exactly as Suzuki, Shaku and many other Buddhist leaders urged them to do. The Background to Suzuki’s ArticleWhile the preceding material introduces Suzuki’s attitude to the Russo-Japanese War and his country’s early colonial efforts, it fails to clarify his attitude toward Japan’s subsequent military activities, especially Japan’s aggression against China initiated by the Manchurian Incident of 1931. This aggression would continue and expand for a full fifteen years thereafter, i.e., until Japan’s defeat in August 1945. Suzuki did, however, write an article, “Bushidō to Zen” (Bushidō and Zen), that was included in a 1941 government-endorsed anthology entitled Bushidō no Shinzui (Essence of Bushidō). With additional articles contributed by leading army and navy figures, this book clearly sought to mobilize support for the war effort, both military and civilian. While not originally written for the book, the fact that Suzuki allowed his article to be included indicated at least a sympathetic attitude to this endeavor though it only indirectly referenced the war with China. 15There is, however, yet another lengthy article that appeared in June 1941 in the Imperial Army’s premier journal for its officer corps. The journal, taking its name in part from its parent organization, was entitled: Kaikō-sha Kiji (Kaikō Association Report) . Although not formally a government organization, the parent Kaikō-sha (lit. “let’s join the military together”) had been created in 1877 for the purpose of creating Imperial Army officers who were to be of “one mind and body.” 16The Kaikō Association Report was a monthly professional journal dating from July 1888. The journal contained articles on such topics as the latest developments in weaponry, mechanization and aviation but also featured yearly special editions devoted to such military events as the Russo-Japanese War and the Manchurian Incident of 1931. In addition, it regularly devoted substantial space to articles on “thought warfare” ( shisō-sen), Japanese spirit ( Yamato-damashii), national polity of Japan ( kokutai), and “spiritual education” ( seishin kyōiku), all key components of wartime ideology. The journal’s ideological orientation can be seen in the articles that both preceded and followed Suzuki’s own contribution. The article preceding his was entitled “The Philosophical Basis of Spiritual Culture,” and included such statements as: “By comparison with Western laws based on rights, our laws are based on duties. By comparison with a [Western] world that operates according to individualism ( kobetsusei), we have created a Japan that operates according to the principles of totality ( zentaisei).” 17 The article following his, entitled “Concerning the Indispensable Spiritual Elements of Military Aviators,” consisted of a speech by officer candidate Yamaguchi Bunji delivered at the graduation ceremony for the fifty-first class of the Japan Army Aviation Officer Candidate School on March 28, 1941. As will be seen, Suzuki’s article fit in perfectly with the strong emphasis on “spirit” in this military journal. “Spiritual education” was one of the most important duties for Imperial Army officers. Officers were required to hold regular sessions with the troops under their command in order to introduce examples from Japanese history of the utterly loyal, fearless, and self-sacrificial warrior spirit. That the historical figures Suzuki introduced had acquired their fearlessness in the face of death through Zen practice was clearly welcomed by the journal’s editors, as it was by the leadership of the Imperial Army. 18The article was published in June 1941, i.e., less than six months before Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. By then Japan had been fighting in China for four years, and while Japanese forces held most major Chinese cities, they were unable, to their great frustration, to either pacify the countryside or defeat the Nationalist and Communist forces deployed against them. The war was effectively stalemated, yet the death tolls, both Japanese and Chinese, continued to rise relentlessly as Japanese forces took the offensive in a bid to force surrender. Suzuki Addresses Imperial Army OfficersSuzuki’s contribution took as its title the well-known Zen phrase: “Makujiki Kōzen,” i.e., Rush Forward Without Hesitation! 19 Note that the complete English translation of Suzuki’s article is included in Appendix I. Some readers may wish to read the translation prior to reading the following commentary though this is not necessary. In addition, Appendix II contains the entire text of the original article in Japanese. In the article’s opening paragraphs we find that Suzuki, like his Zen contemporaries, faced an awkward problem. That is to say, on the one hand he could not help but acknowledge that the Zen (Ch., Chan) school had come to fruition, if not created, in China, a country with which Japan had been at war for some four years. Given the massive death and destruction Japan’s invasion of China had caused, including its priceless Buddhist heritage, how could Japanese Zen leaders justify the ongoing destruction of the very country that had contributed so much to their school of Buddhism? Suzuki addresses this issue by positing Japanese Zen’s superiority to Chinese Zen (Chan) Buddhism. That is to say, Suzuki notes that Zen’s “real efficacy” had only been realized after its arrival in Japan. One proof of this is that in Chinese monasteries meditation monitors use only one hand to hold a short ‘waking stick,’ while their Japanese counterparts hold long waking sticks with both hands just as warriors of old held their long single sword with both hands.

Long ‘waking stick’ |

“The meaning of the fact that the waking stick is employed with two hands is that one is able to pour one’s entire strength into its use,” Suzuki claims. Pouring one’s entire strength into the effort, whether it be waking a dozing meditator or cutting down an opponent, was, for Suzuki, the critical element that Zen and the warrior shared in common. There was no hint of an ethical distinction between the two. Nor did Suzuki acknowledge that in the Sōtō Zen sect, masters continue to employ the short, ‘Chinese-style’ waking stick ( tansaku). This last omission is not surprising in that Suzuki typically either ignored, or dismissed, the practice and teachings of this sect. Suzuki was, furthermore, not content with simply identifying the deficiencies in Chinese Zen, but went on to identify related deficiencies in the “world at large,” including Europe with its single-handed rapiers. That is to say, when non-Japanese fighters wield the sword they do so holding a sword in only one hand in order to hold a shield in the other hand. In so doing, they seek not only to slay their enemy but also to protect themselves, hoping to emerge both victorious and alive from the contest. By contrast, a Japanese warrior holds his sword with two hands because: “There is no attempt to defend oneself. There is only striking down the other.” Was Suzuki accurate in his implied criticism of non-Japanese fighters for attempting to defend themselves in the midst of combat? While Suzuki didn’t name the “countries other than Japan” he was referring to, when discussing this question with undergraduates in my Japanese culture class, a student well versed in the history of European knighthood replied, “As far as Europe is concerned, there is a long history of employing duel-edged “long swords” with both hands just as in Japan. Further, if Japanese warriors were so unconcerned about their own lives, why did they develop what was at the time some of the strongest armor in the world to protect themselves?”

European “long sword” |

I had to agree with this student inasmuch as I had observed the same two-handed long swords when visiting the European sword exhibit housed in Edinburgh Castle in the spring of 2012. In any event, by elevating the alleged fearlessness of Japan’s warriors above that of their non-Japanese counterparts, Suzuki clearly demonstrates his nationalistic stance. A nationalism, it must be noted, that was deeply seeped in blood, both in the past and the war then underway. It should also be noted that the Japanese military had long believed, dating from their victory in the Russo-Japanese War, that they could emerge victorious over a militarily superior (in terms of industrial capacity and weaponry) opponent. In this view, victory over a superior Western opponent, let alone China, was possible exactly because of the willingness of Japanese soldiers to die selflessly and unhesitatingly in battle. By contrast, the soldiers of other countries were seen as desiring nothing so much as to return home alive, thereby weakening their fighting spirit. Suzuki’s words could not have but lent credence to the Japanese military’s (over)confidence. The themes introduced in his article, especially concerning the relationship of Zen to bushidō and samurai, are all topics that Suzuki had previously written about in both Japanese and English. For example, readers familiar with Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture (published in 1938 and reprinted in the postwar period as Zen and Japanese Culture) will recall that at the beginning of Chapter IV, “Zen and the Samurai,” Suzuki wrote: - Quote :

- In Japan, Zen was intimately related from the beginning of its history to the life of the samurai. Although it has never actively incited them to carry on their violent profession, it has passively sustained them when they have for whatever reason once entered into it. Zen has sustained them in two ways, morally and philosophically. Morally, because Zen is a religion which teaches us not to look backward once the course is decided upon; philosophically because it treats life and death indifferently. . . . Therefore, morally and philosophically, there is in Zen a great deal of attraction for the military classes. The military mind, being – and this is one of the essential qualities of the fighter – comparatively simple and not at all addicted to philosophizing finds a congenial spirit in Zen. This is probably one of the main reasons for the close relationship between Zen and the samurai.20 (Italics mine)

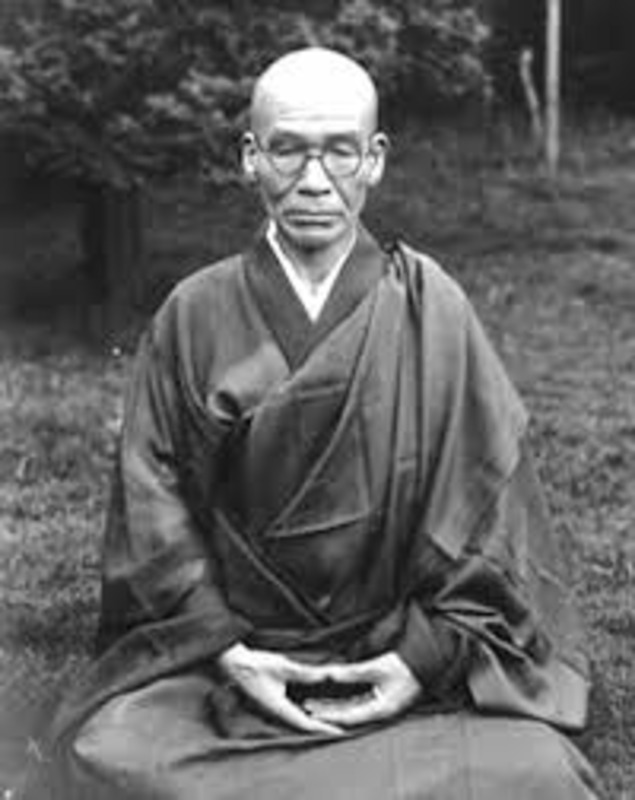

While Suzuki’s officer readers probably would not have welcomed his reference to their “comparatively simple” military minds, the preceding quote nevertheless accurately summarizes the article under discussion here. And to his credit, unlike most other wartime Japanese Zen leaders, Suzuki did not actively incite his officer readers to carry on their violent profession. By contrast, for example, in 1943 Sōtō Zen master Yasutani Haku’un [1885–1973] wrote:

Yasutani Haku’un |

- Quote :

- Of course one should kill, killing as many as possible. One should, fighting hard, kill every one in the enemy army. The reason for this is that in order to carry [Buddhist] compassion and filial obedience through to perfection it is necessary to assist good and punish evil. . . . Failing to kill an evil man who ought to be killed, or destroying an enemy army that ought to be destroyed, would be to betray compassion and filial obedience, to break the precept forbidding the taking of life. This is a special characteristic of the Mahāyāna precepts.21

While these kinds of bellicose statements are notably absent from Suzuki’s writings, the current article, when read in its entirety, makes it clear that Suzuki did in fact seek to passively sustain Japan’s officers and men through his repeated advocacy of such things as “not look[ing] backward once the course is decided upon” and “treat[ing] life and death indifferently.” This leads to the question of just how different Suzuki was from someone like Yasutani given that Suzuki’s officer readers were also encouraged to “pour their entire body and mind into the attack” in the midst of an unprovoked invasion of China that resulted in the deaths of many millions of its citizens? Even readers who haven’t served in the military can readily appreciate the fact that there are two fundamental questions that engulf a soldier’s mind prior to going into battle. First and foremost is the question of self-preservation, i.e., will I return alive? And a close second is - am I prepared to die if necessary? It is in answering the second question, i.e., in providing the mental preparation necessary for possible death, that a soldier’s religious faith is typically of paramount importance. Suzuki was well aware of this, for in promoting Zen training for warriors he wrote elsewhere: “Death now loses its sting altogether, and this is where the samurai training joins hands with Zen.” 22In short, read in its entirety Suzuki seeks in this article to prepare his officer readers, and through them ordinary soldiers, for death by weaponizing Zen, i.e., turning Zen into nothing less than a cult of death. The word ‘cult’ is used here to refer to one of its many meanings, i.e., a religious system devoted to only one thing -- death in this instance. On no less that six occasions throughout his article Suzuki stresses just how important being “prepared to die” ( shineru) is, noting that Zen is “the best shortcut to acquire this frame of mind.” Even if it could be demonstrated that this article was not written specifically for Japan’s Imperial Army officers, little would change, for there cannot be the slightest doubt that Suzuki’s words were intended for a wartime Japanese audience. This is made clear by Suzuki’s statement later in the article that “I think the extent of the crisis experienced then cannot be compared with the ordeal we are undergoing today.” As revealed in Zen at War, by 1941, if not before, all Japanese, young and old, civilian and military, were subject to a massive propaganda campaign, promulgated by government, Buddhist and educational leaders, to accept the death-embracing values of bushidō as their own. Or as expressed by Suzuki in this article: “. . . in undertaking any work one should be prepared to die.” (Italics mine) Here, the question must be asked as to where this Zen shortcut to being prepared to die came from? Did it come from India, Buddhism’s birthplace, or China, Zen (Chan)’s sectarian home? It most definitely did not, for, as already noted, Suzuki tells us that Zen’s “ real efficacy was supplied to a great extent after coming to Japan.” And as he further notes, it was only after arrival in Japan “that Zen became united with the sword.” Unlike the studied ambiguity that typically characterized his war and warrior-related writings in English, and oft-times in Japanese as well, Suzuki was clearly not speaking in this article of some metaphysical sword cutting through mental illusion. Instead, Suzuki was referring to real swords wielded by some of Japan’s greatest Zen-trained warlords as, over the centuries, they and their subordinates cut through the flesh and bones of many thousands of their opponents on the battlefield, fully prepared to die in the process, using Zen as “the best shortcut to acquire this frame of mind.” Interestingly, Suzuki admits in this article that some of the famous Zen-related anecdotes associated with Kamakura Regent Hōjō Tokimune (1251-84) may not have taken place. He writes: “The following story has been handed down to us though I don’t know how much of this legend is actually true.” Compare this admission with Suzuki’s presentation of the same material in Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture. Addressing his English readers, Suzuki wrote that while the exchange between Tokimune and National Master Bukkō (1226-86) is “not quite authenticated,” it nevertheless “gives support to our imaginative reconstruction of his [Tokimune’s] attitude towards Zen.” 23One is left to speculate what Suzuki’s officer readers knew about these allegedly Zen-related anecdotes that his Western readers didn’t know (or perhaps more accurately, weren’t supposed to know). In any event, when reading Suzuki’s repeated claims about the similarities between Zen and the Japanese, one is left to wonder whether it was Zen that shaped “the characteristics of the Japanese people” or, on the contrary, was it “the characteristics of the Japanese people” that shaped Zen? Or perhaps there was some mystical karmic connection that led both of them down the same path – a path in which to “rush forward without hesitation” and “cease discriminating thought” came to mean “one should abandon life and rush ahead”? Furthermore, Suzuki is quite willing to privilege his fellow Japanese with a national character that almost inherently disposes them to Zen. For example, Suzuki claims “there are things about the Japanese character that are amazingly consistent with Zen.” That is to say, the Japanese people “rush forward to the heart of things without meandering about” and “go directly forward to that goal without looking either to the right or to the left.” In so doing they “forget where they are.” If only in hindsight, in reading words like these, it is difficult not be reminded of the infamous and tactically futile “banzai charges” of the wartime Imperial Army let alone the tactics of kamikaze pilots and the manned torpedoes ( kaiten) of the Imperial Navy.

Kaiten (manned torpedo) |

Yet, is it fair to interpret Suzuki’s words as expressions of support for such suicidal acts? One of Suzuki’s defenders who strongly opposes such an interpretation is Kemmyō Taira Satō, a Shin (True Pure Land) Buddhist priest who identifies himself as one of Suzuki’s postwar disciples. Satō writes: “Apart from his silence on Bushido after the early 1940s, Suzuki was active as an author during all of the war years, submitting to Buddhist journals numerous articles that conspicuously avoided mention of the ongoing conflict.” (Italics mine) As further proof, Sato cites an article written by the noted Suzuki scholar Kirita Kiyohide: - Quote :

- During this [war] period one of the journals Suzuki contributed to frequently, Daijōzen [Mahayana Zen], fairly bristled with pro-militarist articles. In issues filled with essays proclaiming “Victory in the Holy War!” and bearing such titles as “Death Is the Last Battle,” “Certain Victory for Kamikaze and Torpedoes,” and “The Noble Sacrifice of a Hundred Million,” Suzuki continued with contributions on subjects like “Zen and Culture.”24

On the one hand, these statements inevitably raise the question of Suzuki’s attitude to Japan’s attack on the U.S. in December 1941. That is to say, what was it that caused Suzuki to stop writing about such war-related topics as bushidō in the early 1940s? Could it have been his opposition to war with the U.S. versus his earlier support for Japan’s full-scale invasion of China from 1937 onwards? Setting this topic aside for further exploration below, the question remains, inasmuch as Suzuki, at least in June 1941, affirmed such things as the acceptability of a dog’s, i.e., meaningless, death, and noted that “in undertaking any work one should be prepared to die” what basis would he have had for opposing such suicidal attacks? Yet another of Chan’s deficiencies is that in China, Chan had been almost entirely bereft of a military connection. By contrast, it was only after Chan became Zen in Japan that it was linked to Zen-practicing warriors. In fact, Suzuki claims that from the Kamakura period onwards, all Japanese warriors practiced Zen. Suzuki makes this claim despite the fact that the greatest of all Japan’s medieval warriors, i.e., Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), was an adherent of the Pure Land sect (J. Jōdo-shū) Buddhism, not Zen. Suzuki also urges his readers to pay special attention to the fact that “Zen became united with the sword” only after its arrival in Japan. For Suzuki it was such great medieval warlords as Hōjō Tokimune, Uesugi Kenshin (1530-78), and Takeda Shingen (1521-73) who demonstrated the impact the unity of Zen and the sword had on the subsequent development of Japan. It was their Zen training that allowed these men to “rush forward without hesitation” and “cease discriminating thought.” If, in the case of Hōjō Tokimune, it can be said that at least his was a defensive war against invading Mongols, the same cannot be said for such warlords as Uesugi and Takeda. They were responsible for the deaths of thousands of their enemies and their own forces, each one of them attempting to conquer Japan. Suzuki lumps these warlords together as exemplars of what can be accomplished with the proper mental attitude acquired through Zen training. Suzuki does not even hint at the possibility that in the massive carnage these warlords collectively reaped, the Buddhist precept against the taking of life might have been violated. | |

|   | | Jcbaran

Posts : 1620

Join date : 2010-11-13

Age : 74

Location : New York, NY

|  Subject: Re: Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D. T. Suzuki Subject: Re: Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D. T. Suzuki  8/5/2013, 4:45 pm 8/5/2013, 4:45 pm | |

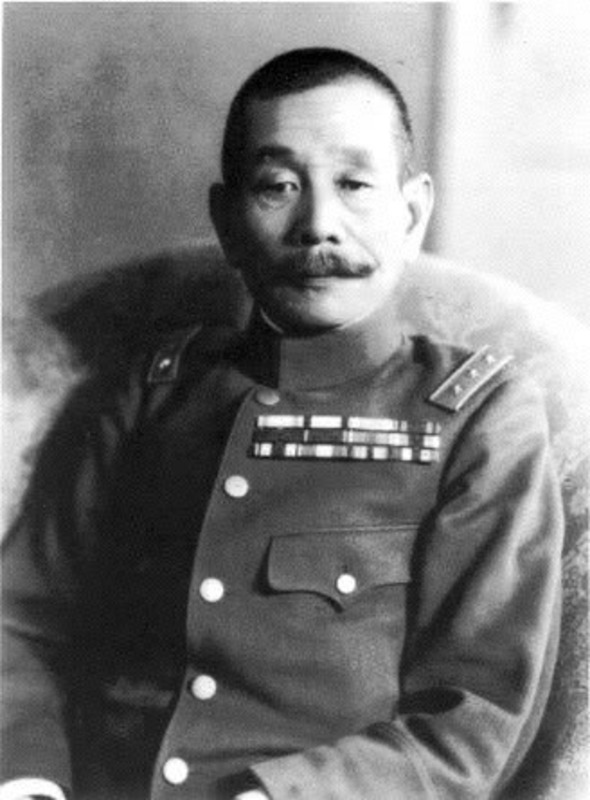

| It is instructive here to compare Suzuki’s words with those of Japan’s most celebrated, Zen-trained “god of war” ( gunshin) of the Asia-Pacific War. I refer to Lt. Col. Sugimoto Gorō, whose posthumous book, Taigi (Great Duty), first published in 1938, sold over a million copies, a far greater number than I first realized when writing Zen at War.

Lt. Col. Sugimoto |

Sugimoto provided the following rationale for Zen’s importance to the Imperial military: “Through my practice of Zen I am able to get rid of my ego. In facilitating the accomplishment of this, Zen becomes, as it is, the true spirit of the Imperial military.” 25 Suzuki was clearly in basic agreement with Sugimoto’s claim. Suzuki argues that it isn’t sufficient to simply discard life and death. Instead, one should “live on the basis of something larger than life and death. That is to say, one must live on the basis of great affirmation.” But what did this “great affirmation” consist of? Suzuki fails to elaborate beyond stating that it is “faith that is great affirmation.” Yet, what should the object of one’s faith be? Once again Suzuki remains silent on this critical question apart from stating that the way to encounter this great affirmation is to dig ever deeper to the bottom of one’s mind, digging until there is nothing left to dig. It was only then, he claims, that “one can, for the first time, encounter great affirmation.” Suzuki admits, however, that this great affirmation is not a single entity but “takes on various forms for the peoples of every country.” Yet, what form does or should it take in a Japan that had invaded and was fighting a long and bitter war with China? As in many other instances of his wartime writings, and as alluded to above, Suzuki maintains a studied ambiguity that makes it impossible to state with certainty what he was referring to. That said, it is clear that nothing in his article would have served to dissuade his readers from fulfilling, let alone questioning, their duties as Imperial Army officers or soldiers in China or elsewhere. Had there been the slightest question that anything Suzuki wrote might have negatively impacted Imperial Army officers who were to be of “one mind and body,” it is inconceivable that the editors of the Kaikō Association Report would have published it. In asserting this, let me express my appreciation to Sueki Fumihiko, one of Japan’s leading historians of modern Japanese Buddhism. In an article entitled “Daisetsu hihan saikō” (Rethinking Criticisms of Daisetsu [Suzuki]), Sueki first presented the arguments made by some of Suzuki’s most prominent defenders, namely, that when some of Suzuki’s wartime writings are closely parsed it is possible to interpret them as containing criticisms of the Imperial Army’s recklessness as well as its abuse of the alleged magnanimity and compassion of the true bushidō spirit. Further, Sueki acknowledges, as do I, that in the days leading up to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor Suzuki opposed war with the U.S. Nevertheless, Sueki came to the following conclusion: “When we frankly accept Suzuki’s words at face value, we must also consider how, in the midst of the [war] situation as it was then, his words would have been understood.” 26As for Suzuki’s opposition to war with the U.S., it is significant that his one and only public warning did not come until September 1941, i.e., only three months before Pearl Harbor. The unlikely occasion was a guest lecture Suzuki delivered at Kyoto University entitled “Zen and Japanese Culture.” Upon finishing his lecture, Suzuki initially stepped down from the podium but then returned to add: - Quote :

- Japan must evaluate more calmly and accurately the awesome reality of America’s industrial productivity. Present-day wars will no longer be determined as in the past by military strategy and tactics, courage and fearlessness alone. This is because of the large role now played by production capacity and mechanical power. 27

As his words clearly reveal, Suzuki’s opposition to the approaching war with the U.S. had nothing to do with his Buddhist faith or a commitment to peace. Rather, having lived in America for more than a decade, Suzuki knew only too well that Japan was no match for such a large and powerful industrial nation. In short, Suzuki’s words might best be described as a statement of “common sense” though by 1941 this was clearly a commodity in short supply in Japan. Be that as it may, when we ask how Suzuki’s Imperial Army officer readers would have interpreted the “great affirmation” he referred to, there can be no doubt they would have understood this to be an affirmation, if not an exhortation, for total loyalty unto death to an emperor who was held to be the divine embodiment of the state. The following calligraphic statement, displayed prominently in every Imperial Army barracks, testified to this: “We are the arms and legs of the emperor.” Due to its ubiquitous nature, Suzuki could not help but have been aware of this “affirmation.” Thus, whatever Suzuki’s personal opinion may have been, he would have been well aware that his officer readers would understand his words to mean absolute loyalty to the emperor. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that in one important aspect Suzuki did part way with other wartime Zen enthusiasts, for not withstanding his emphasis on “great affirmation,” Suzuki does not explicitly link Zen to the emperor. Compare this absence to the previously introduced Lt. Col. Sugimoto who wrote: “The reason that Zen is important for soldiers is that all Japanese, especially soldiers, must live in the spirit of the unity of sovereign and subjects, eliminating their ego and getting rid of their self. It is exactly the awakening to the nothingness ( mu) of Zen that is the fundamental spirit of the unity of sovereign and subjects.” 28By not engaging in emperor adulation in his wartime writings, Suzuki was unique among his Zen contemporaries. Yet this does not mean that he either opposed the emperor system per se or lacked respect for the emperor. This is revealed by the following statement Suzuki made to Gerhard Rosenkrantz, a German missionary visiting Japan in 1939, in the library of Otani University: - Quote :

- We Buddhists bow in front of the emperor’s image, but for us this is not a religious act. The emperor is not a god because for Buddhists a [Shinto] god can be something very low. We see the emperor in an area high above all religions. Trying to make him a god today means a reduction in the status of the emperor. This brings confusion to Buddhism, Shinto and Christianity.29

Thus, even while denying the emperor’s divinity, Suzuki nevertheless justified bowing to the emperor’s image inasmuch he was a personage “in an area high above all religions.” Nor should it be forgotten that Suzuki’s article was not written exclusively on behalf of Imperial Army officers alone. As previously noted, a key responsibility of the officer corps was to provide “spiritual education” for their soldiers. Thus, they were in constant need of additional historical examples of the attitude that all Imperial subjects, starting with Imperial soldiers, were expected to possess, i.e., an unquestioning, unhesitant and unthinking willingness to die in the war effort. Suzuki’s writings clearly contributed to this effort though it is, of course, impossible to quantify the impact his writings had. ConclusionLet me begin this section in something of an unusual manner, i.e., by offering a “defense” of what Suzuki has written in this and similar articles dealing with warriors, bushidō, and the alleged unity of Zen and the sword. That said, while a genuine defense is offered, it is one that nevertheless has a “hook in the tail.” My contention is that Suzuki should not be blamed for having distorted or mischaracterized Zen history or practice, especially in Japan, to make it a useful tool in the hands of Japanese militarists. That is to say, on the one hand Suzuki can and should be held responsible for the purely nationalistic elements in his writings, including collaboration in the modern fabrication of an ancient and unified bushidō tradition with Zen as its core. Yet, on the other hand, the seven hundred year long history of the close relationship between Zen and the warrior class, hence Zen and the sword, was most definitely not a Suzuki fabrication. There are simply too many historical records of this close relationship to claim that Suzuki simply invented the relationship out of whole cloth. Thus, Suzuki might best be described as a skilled, modern day, nationalistic proponent of that close relationship in the deadly context of Japan’s invasion of China. Further, in his English writings, Suzuki did his best to convince gullible Westerners that the so-called “unity of Zen and the sword” he described was an authentic expression of Buddhist teachings. In this effort, it must be said, Suzuki has been, at least until recently, eminently successful. Some Suzuki scholars attempt to defend the most egregious aspects of Suzuki’s nationalist and wartime writings by pointing out that he may have been coerced into writing them by the then totalitarian state. Certainly, there can be no doubt that Suzuki wrote in an era of intense governmental censorship, with authorities ever vigilant against the slightest ideological deviancy. Nevertheless, the most striking features of Suzuki’s substantive wartime writings are, first of all, that they were never censored, and, secondly, their consistency with his earlier writings, dating back to 1896. That is to say, over a span of forty-five years Suzuki repeatedly yoked religion, Buddhism and Zen to the Japanese soldiers’ willingness to die . Certainly no one would claim that Suzuki was writing under fear of government censorship or imprisonment in 1896. Where Suzuki did break with the past close relationship of Zen to the warrior class was in transmuting this feudal relationship into one encompassing Zen and the modern Japanese state albeit not specifically with the personage of the emperor. It is in having done this that he can rightly be identified as a “Zen nationalist.” 30 Needless to say, he was only one of many such Zen leaders, and when compared with the likes of Yasutani Haku’un, Suzuki was clearly less extreme. 31 When we inquire as to the cause or reason for the close relationship between Zen, violence, and the modern state that Suzuki promoted, the answer is not hard to find. In his book, Buddhism without Beliefs, Stephan Bachelor provides the following explanation regarding not just Zen but all faiths, i.e., "the power of organized religion to provide sovereign states with a bulwark of moral legitimacy. . .” 32 To which I would add in this instance, the power of Zen training to mentally prepare warriors/soldiers to both kill and be killed. Or as Suzuki would have it, to “passively sustain” them on the battlefield. Having said this, I would ask readers to reflect on the historical relationship of their own faith, should they have one, to the state, and state-initiated violence. Was Batchelor correct in his observation with regard to the reader’s faith? That is to say, have not all of the world’s major religions, like Buddhism, provided moral legitimacy for the state’s use of violence? Is Buddhism unique in having done this or only one further example of Chicago University Martin Marty’s insightful comment that “one must note the feature of religion that keeps it on the front page and on prime time -- it kills”? 33To answer yes to any of these questions is not to excuse, let alone justify, Zen or any other school of Buddhism’s moral lapses in this or any instance. Yet, it does suggest the enormity of the problem facing all faiths if they are to remain true to their tenets, all of which number love and compassion among their highest ideals. At the end of his life Buddha Shakyamuni is recorded as having urged his followers to “work out your salvation with diligence.” In the face of continuing, if not increasing, religious violence in today’s world, is his advice any less relevant to all who, if only in terms of their own faith, seek to create a religion truly dedicated to world peace and our shared humanity? Brian Daizen Victoria is a Visiting Research Fellow, International Research Center for Japanese Studies (Nichibunken) in Kyoto, Japan. Appendix I (Complete English Translation of Article) - Quote :

- “Makujiki Kōzen” (Rush Forward Without Hesitation).34

I think that most scholars and informed persons will agree that Zen thought is one of the most important factors forming the basis of Japanese culture. Although Zen originally came from India, in reality it was brought to fruition in China while its real efficacy was achieved to a great extent after coming to Japan. The reason for this is that there are things about the Japanese character that are amazingly consistent with Zen. I think the most visible of these is rushing forward to the heart of things without meandering about. Once the goal has been determined, one goes directly forward to that goal without looking either to the right or to the left. One goes forward, forgetting where one is. I think this is the most essential element of the Japanese character. In this, I think, Zen is one of the strongest factors allowing the Japanese people to rush forward. For example, the Japanese hold a sword with both hands, not one. Although I have not researched this question extensively, in countries other than Japan they use only one hand to hold a sword. Further, they use their left hand to hold a shield. That is to say, they use one hand to defend themselves while they use the other hand to strike the enemy. Although my knowledge is limited, this is what I think as I observe the world at large. However, a sword in Japan is held with two hands. There is no attempt to defend oneself. There is only striking down the other. That is to say, one discards the body and plunges toward the other. This is the Japanese people’s way of doing things. And it also happens to be the Zen way of doing things. I became aware of this from [my experience in] a Zen meditation hall. In a Japanese meditation hall there is something called a waking stick ( keisaku). A waking stick is made of wood and is about 121 cm long. It is an implement used to strike someone who is practicing zazen in a situation where their shoulders become stiff from having put too much strength into them. At that time, both hands are used to wield the waking stick. In China, too, there is a kind of waking stick. Although I don’t know what was used in the past, the waking stick that is used today is approximately 76 cm long and is used for striking with only one hand. However, in Japan we use both hands. Given this, it may be that only at the time the waking stick first arrived in Japan was it held with one hand. Then, after coming to Japan, it became used with two hands. The meaning of the fact that the waking stick is employed with two hands is that one is able to pour one’s entire strength into its use. That doesn’t mean that it is impossible to pour one’s entire strength into wielding the waking stick with only one hand, but I think that using both hands, rather than one, is better and enables one to more fully put one’s entire strength into the effort. In Europe there is something known as fencing which employs a thin blade using only one hand. In this instance the left hand is simply held high above the shoulder while one thrusts forward with all one’s might. However, the place at which one’s power emerges is the very tip of the blade being held with one hand. In a situation where one holds a sword with both hands, there is no doubt that, in comparison with holding it with one hand, one is better able to exert one’s full strength. While I don’t know what a practitioner of swordsmanship would say about this, seen from the point of view of an outsider like myself, this is how it appears. Although it is said that [the famous swordsman] Miyamoto Musashi used two swords, I have heard that in an actual swordsmanship match he never used two swords though I don’t know how true that is. Furthermore, I think that in a situation where Musashi used two swords, one of them was simply used for defense.

Miyamoto Musashi |

It was not a question of both swords being used independently by each hand, but a situation in which the movement of one mind expressed itself, depending on the situation, with each of two swords. For that reason it was not a question of thrusting with each one of two swords but of either thrusting with both hands or slicing with both hands at the same time. The truth is that while he appeared to use two swords, I think the reality was that he employed the swords in both hands as if he were grasping a single long sword. Be that as it may, the character of the Japanese people is to come straight to the point and pour their entire body and mind into the attack. This is the character of the Japanese people and, at the same time, the essence of Zen. - Quote :

- The Meaning of Being Prepared to Die

The Hagakure states that bushidō means to be prepared to die. That is to say, in undertaking any kind of work it is said that one must “die first.” It may be that in such a situation there is something known as a dog’s [i.e., pointless] death. It may be that when it is the right time to die one should simply die in that situation. In any event, what the Hagakure states is that even a dog’s death is all right. That is to say, in undertaking any work one should be prepared to die. This is the way it is written [in the Hagakure], and seen from a psychological point of view this is, I think, truly the way it ought to be. In human beings there is, in general, something known as the self. The concept of an individual self is not something easily gotten rid of. In Buddhism this is something known as illusion. Illusion is made up of fine threads that are strung together in such a way as to make it impossible to move freely. Although the threads are extremely fine, one is incessantly caught in their grasp. The decision to be prepared to die means the cutting of these threads. To truly be able to do this is not possible simply by deciding to die in the course of working. There is something far deeper than this that must be done. In this connection there is the following story. In medieval Europe there was a lady who decided to enter a nunnery to engage in religious practice, but her family wasn’t willing to let her go. Although a number of years passed, she had no opportunity to make good her escape. Then, one night a good opportunity came, and she managed to leave home. She intended to go to a monastery and spend the rest of her life in religious practice. Upon leaving home she took some money with her because she felt that without money she wouldn’t be able to buy something to eat along the way. What can be said in this regard is that her attraction to money was a symbol of just how hard it was for her to overcome attachment to a world she claimed to have cast aside. At that point the lady thought to herself how lamentable it was that in the midst of having discarded the world, her parents and siblings in order to dedicate herself to God, she was still attached to money. She became worried about the money she had taken, thinking that she would be unable to accomplish anything. Thinking to herself that she had to cast aside the money, she decided to get rid of it. As a result, the story goes, her mood underwent a drastic change, and she acquired a frame of mind in which she was readily able to do what had to be done. In the past, there was a Buddhist priest by the name of St. Kūya. St. Kūya constantly recited the phrase, Namu Amida-butsu [Hail to Amitābha Buddha] , as he walked about. There is a story that at one point someone asked him, “What is the purpose of Buddhist practice?” He replied, “Discard everything!” as he quickly walked past. This “discard” is the main point of Buddhism and also the spirit of Zen. Discarding a sum of money is the same as discarding one’s life. Now in the case of the Christian woman, money represented the same bond of life and death as it does to an ordinary warrior who fails to become free due to his routine mental state. In the past, a warrior was someone who discarded his life on behalf of his master. It meant that he could discard his life in the midst of battle. It may well be that discarding one’s life in the midst of battle is relatively easy, for I think it isn’t too difficult for ordinary people to discard their lives when the entire environment calls for it. However, what is difficult is to give up one’s life in peacetime. That is to say, when the world is at peace. It is then that it is difficult to have a frame of mind in which one is prepared to give up everything one has. Yet, someone who is able to do so is completely free, though this mental state is quite difficult to acquire. In the past they discussed this problem in China, too. A nation would fall, they said, in a situation where warriors, becoming cautious, were reluctant to lose their lives while, at the same time, government officials sought to enrich themselves. Should there be military men who were reluctant to lose their lives they would be of no use whatsoever. Should there be any like that, they ought to stop being military men. When this is applied to government officials, this is not simply a question of their loving money or fame. Rather, I believe it is possible to say that they, too, must try to discard their lives. In the past there was no special class known as government officials, for warriors were both military men and government officials. In peacetime warriors engaged in politics in government offices while in wartime they took up the sword and charged ahead. Military men became political figures, and political figures were originally military men. In any event, it isn’t easy to acquire the mental state in which one is prepared to die. I think the best shortcut to acquire this frame of mind is none other than Zen, for Zen is the fundamental ideal of religion. It isn’t simply a question of being prepared to die, as Zen is prepared to transcend death. This is called the “unity of life and death” in which living and dying are viewed as one. The fact that these two are one represents Zen’s view of human life and the world. In the past there was [a Zen priest by the name of] National Teacher Sekizan. A story describes a disciple who asked him, “I and others are imprisoned by life and death and cannot become free. What can we do to realize the unity of life and death?” Sekizan taught him, saying, “You don’t have such trivial things as life and death!” - Quote :

- Rushing Forward Without Hesitation

At present I am in Kamakura where I live within Engakuji temple’s precincts. I would like to discuss Hōjō Tokimune and National Teacher Bukkō who constructed Engakuji temple. Tokimune became regent when he was only eighteen years old and died at the age of thirty-four. His rule of seventeen years began and ended with a foreign policy directed against the Mongols. Were something like this to take place today when transportation is readily available, I think it would be easy to get information about the enemy. However, in the Kamakura period it was almost impossible to get information about either the enemy or their disposition. Still, communication was possible through people who either went to China from Japan or came to Japan from China, so I think there was quite a lot of information available. That said, in one sense one nevertheless encountered a large unknown. The large unknown was exactly when and under what conditions the enemy would arrive. I think that as far as Tokimune, their opponent, was concerned, it was not sufficient to be just politically or militarily prepared. One is able to fight well only when one knows both the enemy and those at one’s side. Because it was an unknown enemy, it was very difficult to determine the size of the force that would be sufficient to oppose them. Nevertheless, it was a situation in which, moment by moment, the crisis drew nearer. I think the extent of the crisis experienced then cannot be compared with the ordeal we are undergoing today. I would like to imagine the frame of mind that made it possible to surmount the hardships of those times. At long last, a massive Mongol army invaded on two occasions. In opposing them, Tokimune never once set foot out of Kamakura. The war took place within the confines of [the southern island of] Kyushu. Today we wouldn’t describe such a place as being far away, but rather, close at hand. However, in the Kamakura period, in an age when travel was difficult, it must be said that Kyushu was indeed a distant place. Further, although Tokimune didn’t relocate the Shogunate [military] government, he was still able to gather soldiers together from throughout the country of their own free will. Tokimune didn’t accomplish this by himself. Instead, it was the nature of Kamakura in those days that made it possible for him, due to his virtue, to unite all the people together in a harmonious whole, not simply through the exercise of his power. I think this was not something he was able to do on his own. True enough, there were Shinto shrines flourishing throughout the country, not to mention [the protection of] various gods and Buddhas. Yet, while it is fine to pray to them, the power of prayer by itself would not serve to defeat the enemy. I think one must have material goods such as tanks to counter tanks in order to accomplish this. When the Mongolian soldiers attacked, merely praying for their death would be insufficient. That is to say, it was necessary to prepare a sufficient military force. It is said there was a divine wind [ kamikaze], but the blowing of such a divine wind was recognized only after the fact, not before it occurred. That is to say, it was impossible to depend on a divine wind before it had blown. If, in anticipation of a divine wind, Tokimune had failed to make preparations, it may well be that the Mongol soldiers would have advanced as far as Kyoto at some point. Although people like myself are not familiar with strategic military terminology, I am sure Tokimune must have had a plan prepared consisting of a first, second and third stage. I’m sure he wouldn’t have done something so reckless as to construct a fortress and then tell everyone to take it easy. If this is true, then he simply didn’t remain in Kamakura unperturbed. Being the type of person he was, there can be no doubt that he must have first thought of the preparations and methods that would allow him to remain calm. It is unthinkable that it could simply be a question of his attitude or daring alone. Without observing the other side, nothing can be accomplished. Even if there were such a thing as bravery unconcerned about the other side, there must be appropriate methods for the effective utilization of such bravery. If it were possible to pray for the death of the enemy without using appropriate methods, i.e., by means of spirit alone, it may well be that there are enemies who can be killed in this way. But it may also be there are enemies who cannot be killed through the power of prayer. This way [of defeating the enemy] simply can’t be counted on. There must be other effective methods that can be utilized. I believe it is only common sense to think that Tokimune must have possessed such methods. While my knowledge of history is limited, not to mention that I have no knowledge of military strategy, nevertheless, as someone with common sense, what I have said is quite possible when one considers the state of affairs at that time. The following story has been handed down to us though I don’t know how much of this legend is actually true. Nevertheless, it is clear that even if a legend didn’t actually occur at the time and place claimed, there was a background to asserting that the events in the legend actually happened. If may well be that not all historical facts that have been transmitted down to us are true. But the reason we accept something that didn’t actually happen is because we must have already prepared something within our minds that allows us to accept it as fact. This becomes reflected in the environment and is transmitted to us as fact. And for this reason persons who hear facts like these can immediately believe them. The significance of the preceding discussion concerns the moment when, having received news that the Mongolian soldiers were on their way, Tokimune approached National Master Bukkō to inform him that a fearful situation confronted him. In response National Master Bukkō immediately said, “Rush forward without hesitation!” In addition, there is also this exchange between the two. Tokimune asked National Master Bukkō, “When various incidents occur, and I am perplexed by things that happen here, and by things that happen there, what frame of mind should I have in seeking to deal with them?” It is said that National Master Bukkō immediately responded, “Cease discriminating thought!” Either expression, i.e., “rush forward without hesitation” or “cease discriminating thought,” is fine. Further, whether National Master Bukkō actually said these words or, instead, Tokimune expressed his own belief, is likewise fine. In any event, it is sufficient to imagine that at some point National Master Bukkō and Tokimune had a conversation like this. These exchanges point to the fact that by the time the Mongol soldiers arrived, Tokimune was already mentally prepared. I think this means there was no need for Tokimune to make a specific visit to National Master Bukkō to show his determination. I imagine that these exchanges, like something out of a drama or novel, were created in order to effectively reveal his frame of mind. This is because Tokimune had already undergone sufficient mental training during the course of his life. This wasn’t a situation in which the matter would be resolved simply by asking something like what I should do now that the Mongols have arrived. The greater the power someone has developed is, the greater its application is to be commended. As we have all already experienced, momentary pretense is of no use. Leaving aside the question of whether the preceding exchanges actually occurred at a particular point in time, there can be no doubt that Tokimune was wont to use “rush forward without hesitation” and “cease discriminating thought” as the core of his methods for mental training. In one sense it can be said that “rush forward without hesitation” and “cease discriminating thought” are characteristics of the Japanese people. Their implication is that, disregarding birth and death, one should abandon life and rush ahead. It is here, I think, that Zen and the Japanese people’s, especially the warriors,’ basic outlook are in agreement. - Quote :

- The Essence of Things

In China, Zen served, on the one hand, as a kind of philosophy and, on the other hand, as religious belief. Although in China there were quite a few scholars, religious persons and artists who practiced Zen, it appears that it did not become the basis of Chinese life. In particular, one hears almost nothing about military men and warriors who practiced Zen. If we consider Wang Yangming to have been a military man, his main profession was nevertheless that of a scholar or, more specifically, a scholar of Confucianism. However, it is true that he did fight and was very successful. As far as military men who practiced Zen in China, he was, I think, probably the only one to have done so. However, when Zen came to Japan things were completely different. In Japan warriors have, for the most part, practiced Zen. Especially from the Kamakura period [1185-1333] through the Ashikaga [1337-1573] and Warring States period [1467-1567], it is correct to say that all of them practiced Zen. This is clear when one looks at such famous examples as [warlords] Uesugi Kenshin, Takeda Shingen, and others. And then, with the advent of the Tokugawa period [1603-1868], we find Zen was very popular among famous painters. I believe one should pay special attention to the fact that Zen became united with the sword. When we look at the inner essence of swordsmanship, or its secret teachings, or its oral transmission, it can be said that all of them added an element of Zen. There is no need to give various examples of this inasmuch as those who have researched this question even slightly would readily agree. That said, one of the clearest examples can be seen in the relationship between [Zen Master] Takuan and [sword master] Yagyū Tajima no kami. And while not as well known as Yagyū Tajima-no-kami, there is also the relationship between Katō Dewa-no-kami Taikō, Lord of the Iyō Ōzu [region], and Zen Master Bankei. Lord Katō of Ōzu was an expert with a spear. While I don’t know how skilled Zen Master Bankei was with a spear, given that he was a Buddhist priest I think he may not have been all that skilled. Nevertheless Katō Taikō received a secret transmission concerning the spear from Zen Master Bankei. Whether we are talking about the inner essence of swordsmanship or that of politics, or battle, the most important question for all persons is that of the self. One must begin to discard the individual self. When you have something called a self you are slave to the self. This is because the self is something that, by nature, is born and dies. If one attempts to distance oneself from life and death, one must not have a self. One must transcend the self. However, this is not a question of discarding or eliminating the self. In order to eliminate the self one must find something that is larger than the self. Human beings are unable to accomplish anything by being passive. On the other hand, when they actively affirm something they are able to act. By nature human beings die through negation and live through affirmation. One mustn’t simply discard life and death but, instead, live on the basis of something larger that life and death. That is to say, one must live on the basis of great affirmation. If it were simply a question of discarding that would be negation, not affirmation. To be more precise, it is faith that is great affirmation. One must encounter this great affirmation. Depending on the person, this great affirmation can take many forms. Further, I think that it takes on various forms for the peoples of every country. Still further, I think that it takes on various forms depending on the social class of the person in question. Nevertheless, if it is a question of true affirmation, it must consist of digging deeply to the bottom of one’s mind, then more deeply and still more deeply to the point where there is nothing left to dig. It is only then that one can, for the first time, encounter great affirmation. When this is expressed in a Confucian context it is called sincerity. In the Shinto tradition it can be called being without artifice. Whether it is called sincerity or being without artifice, these are not things that can be acquired in a whimsical manner. Nor are they things that, as ordinary people never tire of saying, can be united together. This great affirmation is something that people must experience for themselves, not bragging about it boisterously and indiscriminately in front of others. This must be thoroughly understood. Rather than rambling on about this great affirmation in front of others, it should be stored in one’s mind and taken out and used as necessary. A 17 th century] scholar by the name of Yamaga Sokō [1622-85] wrote a work entitled Seikyō-yōron [A Summary of Confucian Teachings]. In this work he defines sincerity as meaning “something unavoidable.” Sincerity, then, is something that cannot be avoided. The meaning of “something unavoidable” is that one digs deep, deeper and still deeper into the innermost recesses of the mind. Having reached the culmination of digging deep into the mind, one encounters a moving object. The moving object encountered is “something unavoidable.” That which people never tire of talking about is not “something unavoidable,” but rather something that is nothing more than an aspect of the self. Therefore, it is not a moving object that comes from the innermost depth of the mind. Further, Yamaga Sokō states “something unavoidable” is “something natural.” This “something natural” ought to be seen as the equivalent of “being without artifice.” Finally, there is this poem. In the Tokugawa era there was a person by the name of Zen Master Shidō Bunan. Among his poems is the following: - Quote :

- Become a dead man while still alive and do so thoroughly.

Then you will be able to live as your heart leads you.35 There is no need for further explanation. I leave this up to my readers to interpret as they wish. | |

|   | | Jcbaran

Posts : 1620

Join date : 2010-11-13

Age : 74

Location : New York, NY

|  Subject: Re: Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D. T. Suzuki Subject: Re: Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D. T. Suzuki  3/31/2014, 9:52 am 3/31/2014, 9:52 am | |

| Rude Awakenings: Zen at War

Home » Buddhist World » Rude Awakenings: Zen at War

Posted on Mar 24, 2014

from: http://www.wiseattention.org/blog/2014/03/24/rude-awakenings-zen-at-war/

Zen at War revealed to people in the West the extent of Buddhist collusion with the Japanese War Effort in WW2. This article explores the issues that raised with the book’s author, Brian Victoria by Vishvapani

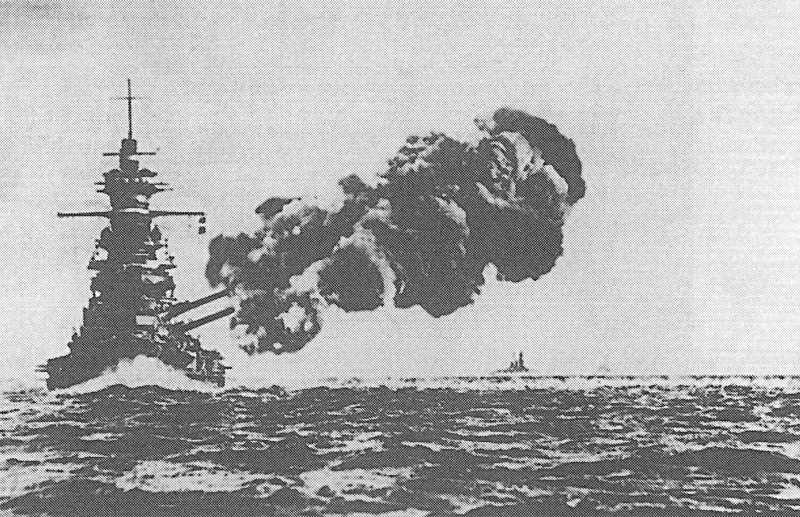

When dawn broke over Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941 it brought with it waves of Japanese bombers. Their surprise attack on the American naval base brought the us into the Second World War and initiated a conflict that ended only when nuclear bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Every American schoolboy knows that much. But, while Americans counted their losses and vowed revenge, Japanese Buddhists found a special cause for celebration:

"December 8th [the date of the attack in Japan] is the holy day on which Shakyamuni realised the Way, and [for this reason] it has been a day for commemorating the liberation of humankind. It is exceedingly wonderful that in 1941 we are able to make this very day also a holy day for commemorating the eternal reconstruction of the world. On this day was handed down the Great Imperial Edict aimed at punishing the arrogant United States and England, and news of the destruction of American bases in Hawaii spread quickly throughout the world.’

These words by the Buddhist writer Hata Esho, which were published in a Zen journal called Dogen (named after the founder of the Soto Zen school), would not have surprised their readers. The Zen establishment, indeed the leadership of all the main Buddhist schools in Japan, had been enthusiastic supporters of their Meiji rulers since the late 1900s, and were wholeheartedly behind the Japanese war effort.

A generation later the sons and daughters of the servicemen who had fought the Japanese took to the streets and campuses of the us to protest against the Vietnam War. Their rebellion turned into a rejection of mainstream western society, and a whole generation looked outside its culture for guidance and meaning. Many were captivated by the mysterious tradition of Japanese Zen, with its philosophy of going beyond the rational mind – beyond all dualism – to reach the simplicity at the heart of life. They took up its practice of zazen, or formless sitting meditation; and were entranced by the benign figures of such Zen masters as Yasutani Roshi and the writer DT Suzuki.

Thirty years on, the sixties generation are leaders of the western Buddhism that has spread across Europe and the us. Many have yoked their Zen practice to their concern for social justice and have declared the emergence of a new ‘Engaged Buddhism’. But the repressed history of the complicity of Japanese Buddhism in the country’s militarism and nationalism has returned to trouble modern Buddhists. The process started in Japan, but it has spread to the West. After many years of declaring that ‘no war has ever been fought in the name of Buddhism’, western Buddhists are having to acknowledge that this is untrue.

The fuse was lit in the West in 1997 with the publication of Zen at War, a careful but implacable account of Japanese Buddhism’s complicity in the country’s fanaticism, militarism and war effort up to 1945. The author, Brian Victoria, started to practise Zen while in Japan in 1961 and formally entered the Soto Zen priesthood in 1964, receiving the Dharma name ‘Daizen’. For Victoria, commitment to Zen went hand-in-hand with opposition to violence, particularly the Vietnam War, and his activism took him across Asia. But one day Zen Master Niwa Rempo summoned Victoria to his office to inform him that he was must cease his peace protests or lose his priestly status, adding, ‘Zen priests don’t get involved in politics.’

Victoria ignored the warning and none the less remained a priest, but his interest had been aroused. What, he wondered, was the relationship between Zen and politics? As his research progressed he discovered a history that his Zen teachers had failed to mention and which they were reluctant to discuss – the deep yet hidden responsibility of his own religious tradition for Japanese militarism. Zen at War is the product of his researches over the following 25 years; he now teaches at the University of Adelaide in Australia. There is no space here to rehearse Victoria’s arguments in full, nor to present his evidence; I conducted an e-mail interview with him but I’m in no position to verify his assertions. It is worth knowing, however, that his work is buttressed by that of many other scholars, and that its essential truth has not been challenged.

The essence of the charge in Zen at War is that from the end of the 19th century until 1945, almost the entire Japanese Buddhist establishment – not just Zen Buddhists – were vigorous supporters of the war effort and the militaristic society from which it grew. For instance, during the Russo-Japanese war of 1906 the well-known Buddhist scholar-priest Inoue Enryo argued that ‘If [the Russian army] is the army of Christ, ours is the army of the Buddha’. By the 1930s Buddhist teachers were advocating an ‘Imperial Way’ Zen, based, as Zen Master Yamazaki Ekiju put it, on the belief that ‘Japanese Buddhism must be centred on the emperor. … Buddhism, including Shakyamuni’s teachings, must conform to the national policy of Japan.’

Buddhist leaders willingly dubbed Japan’s campaigns in World War Two ‘a holy war’, and played a significant role in maintaining morale: ‘If ordered to tramp: march, march, or shoot: bang, bang,’ as Harada Daiun, a famous Zen master wrote. ‘This is the manifestation of the highest Wisdom.’

As the military situation deteriorated, and nationalism merged into desperation, Buddhist rhetoric even played its part in finding volunteers to be kamikaze pilots. One Soto priest wrote in 1943: ‘The source of the spirit of the Special Attack Forces lies in the denial of the individual self and the rebirth of the soul, which takes upon itself the burden of history. From ancient times Zen has described this conversion of mind as the achievement of complete Enlightenment.’ This, for Victoria, is the culmination of the military tradition of Zen – the equation of the pilot’s willing death with the highest goal of the spiritual life.

Victoria’s charge is not simply that Zen teachers were swept along by the nationalist tide. That would be unsurprising and understandable. During the First World War, for example, belligerent European nations on both sides had the support of churches of many denominations. Virtually all religions that have become the dominant faith of a nation have had to come to terms with the military dimension of the nation’s life. But Victoria told me that his forthcoming book Zen War Stories will demonstrate even more clearly that Zen teachings played a central role in instilling the military ethos and offering moral support to the military. ‘Japanese military leaders deliberately set out to inculcate a Zen-inspired attitude in Japanese troops as they raped and pillaged their way through Asia from 1931 to 1945, killing between 10 and 20 million men, women and children. This was done with the complete and unconditional support of all Japan’s Zen leaders.’