Lost in Time in England’s NortheastBy JANE SMILEY JUNE 6, 2014

Durham Cathedral seen from a hill overlooking the town. Credit Andrew Testa for The New York Times My gateway drug to serious Anglophilia was horses — the British Pony Club Manual of Horsemanship, my English saddle made by Barnsby — but the addiction was truly about words. What, for example, could “Hounds, gentlemen, please” possibly mean? This was a sign along the roadside near the stable where we kept my horse outside St. Louis. I turned it over in my mind for months before I understood that drivers were being asked to slow down if foxhounds were in the vicinity.

Then there was Dickens, then there was Austen and Eliot, then there was a little trip to London my senior year in high school, which included Westminster Abbey, Trafalgar Square and Oxford Street. Then there was the history sunk deep into place names like Pemberley, the estate in “Pride and Prejudice” where Mr. Darcy eventually brings Elizabeth, with its Anglo-Saxon roots of “Pem” (high) and “ley” (field), or Chesney Wold, the Dedlock estate in “Bleak House,” containing “ney (island) and “wold” (woodland).

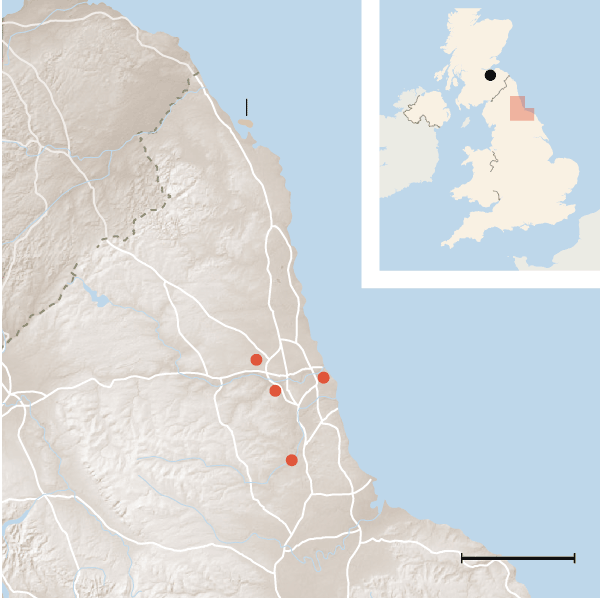

20 miles

By the time I found myself scraping away the soil on an archaeological dig at the cathedral in Winchester, the summer after college, my real self was medieval, and getting older. I was not yet completely at home in those narrow Winchester streets, but I knew I could be with a little effort.

I can’t say when it fell away, only that for years now, I’ve preferred going to France and (if I want a little taste of Britain) Aquitaine in the southwest, where the English and the French fought the Hundred Years’ War off and on between 1337 and 1453. But I was invited to Durham University in the northeast of England in March, and on the principle that I never turn down a free airline ticket, I went, imagining that darkness and rain were the main things awaiting me. The first item that I packed was an umbrella.

The sun did go down not long after I climbed aboard the East Coast train out of King’s Cross Station, minus my suitcase, which was stranded in Los Angeles. The coach was achingly cramped, and my seat mates gossiped incessantly about their fellow lawyers, wherever it was that they worked.

St. Aidan’s College (one of 16 university colleges scattered around Durham) was modern and spare; it could have been in Wisconsin. I went to bed longing for California. Or Toulouse.

Streets leading to Durham Cathedral. Credit Andrew Testa for The New York Times

But the next day, when I threw back the curtains in my chilly room, the sunshine was alluring and brilliant. St. Aidan’s, it turned out, was on a hill overlooking Durham Cathedral, a distant stony point in a landscape shivering with green. I had a day to myself, and a day is perfect for exploring this compact town.

Durham is not much of an international tourism destination, perhaps because Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Dickens and J. K. Rowling are all from elsewhere (though Durham Cathedral did stand in for Hogwarts in the first two Harry Potter movies). Even those paradigmatic northerners, the Brontës, grew up 90 miles to the southwest of Durham. What might get you off the East Coast train before Edinburgh is the lost-in-time peacefulness of the broad landscape and the picturesque homeliness of Durham itself, which was founded in 995 by monks who were carrying the remains of St. Cuthbert, one of England’s first native-born saints, from Lindisfarne to this peninsula safe within the embrace of the looping Wear River. The monks had been carrying the remains off and on for 120 years, doing their best to avoid Viking attacks. Legend has it that when the bier became impossible to lift, the monks happened upon a woman looking for her dun cow, who led them, now miraculously able to lift the bier, to the current site.

A 10-minute downhill walk brought me to a white gate, then a small road leading to the footbridge to South Bailey. The weather was cool and clear — Durham had escaped the downpours of the previous month and the floods along the Thames that I saw when my plane descended toward Heathrow. The Wear glinted neatly within its banks as I approached the bridge, admiring the way luxurious and wild vegetation crowded against every stone wall, interfered with every view, asserted itself in the form of mistletoe growing up every tree, dead leaves piled in every depression, shoots of early spring flowers thrusting up here and there, not yet blossoming, though full of promise.

Across the bridge, the streets were narrow and well used. Durham is hilly and the houses pressing against the sidewalks exude a sense of quiet privacy. Even the cathedral appears suddenly (to the left up Dun Cow Lane), its patch of vivid green dotted with dark stone graves and memorials. The facade glittered grandly in the morning light, but the doorway was modest, almost mysterious.

On Holy Island, the ruins of Lindisfarne Priory with the castle beyond. Credit Andrew Testa for The New York Times

The cathedral, begun in 1093, is the place in England where architects first solved the problem of enclosing the nave by using quadrant arches to bear the weight of the roof, thus founding the Gothic style (though the most famous Gothic cathedrals, such as York Minster and Chartres Cathedral, date from 200 years later). The cathedral has a rough, homely look, the interior dark brown, welcoming.

On the morning I visited, the Chapel of the Nine Altars, where St. Cuthbert’s remains are buried at the east end of the nave, was filled with sunshine. In a quieter spot at the west end, the Galilee Chapel, was the unexpected (to me) tomb of Bede (672-735), the Anglo-Saxon historian who wrote “An Ecclesiastical History of the English People,” as well as numerous commentaries on the Bible, several saints’ lives and three scientific treatises. My scalp actually tingled as I stood before Bede’s 1,200-year-old remains — most of his contemporary authors, of “Beowulf,” of “The Seafarer,” of “The Dream of the Rood,” are unknown. I felt some Anglophilia coming on. My deep love for English literature has never wavered, and here was its very root.

Durham’s shopping district has its Topshop and its Marks & Spencer department store, like every other town in Britain, but because Durham is so small, the shops have a cozy, ancient air, as if you might find something lost for hundreds of years if only you looked closely enough. For lunch, I had soup at Vennels, a local cafeteria in a very slender back alley (cash only). The potato soup and the homemade buns were delicious, and, as with the Chapel of the Nine Altars, the sunshine was pouring in in an unlikely way, through windows near the ceiling. At the nearby Edinburgh Woollen Mill, I found that hidden treasure: a lightweight lavender sweater that made me not care any longer that my suitcase was still astray.

Across a spacious green quadrangle from the cathedral is Durham Castle, complete with an imposing octagonal keep that crowns the hillside and looms over the square, but is beautifully framed by flowering trees. The castle, now a university college, was once occupied by the bishop of Durham, built in the 11th century in a vain attempt by the Normans to exert power over the inhabitants of the north. It suggests another attractive characteristic of the counties of Durham and Northumberland: legendary intransigence.

Wooden poles mark a walking route between the mainland and Holy Island. Credit Andrew Testa for The New York Times

I walked out of Durham over the Elvet Bridge and wandered a few minutes later into the cemetery of the Parish Church of St. Oswald (parts of which date back to the late 12th century, but which was extensively rebuilt in the 19th century), once again into a fertile and relatively untamed meadow of long grass, trees and gravestones, with intermittent views across the river toward the cathedral. As small and old as it is, Durham is chock-full of hiding places, wildflowers, sudden views of sky and meadows. It did not remind me of anywhere else I have been in Britain.

The day after the conference, it took my companion, a professor at St. Aidan’s, and me a couple of hours to retrace the 120-year journey of St. Cuthbert’s remains. These days, the causeway to Lindisfarne (now called Holy Island) is a paved road across mud and sand flats; visitors are strictly warned to be aware of the tides and to cross only during safe crossing times. The first thing I saw as we started across the causeway was a small wooden tower beside the road — our refuge should we be caught unawares and have to abandon our car. Beyond the flats, the island juts upward, March green along the hillsides, but mostly treeless and open to the crisp air.

The north of England was the site of sustained religious conflict in the seventh and eighth centuries — paganism of a basically Scandinavian model was flourishing; the pope wanted to claim the area, but so did Celtic Christians, who adhered to a different calendar. St. Aidan did convert the population and several important kings, but is said to have chosen Lindisfarne because he did not want his local king to be able to tell him what to do. No ruins of the original priory remain, but as I gazed upon the beautiful red sandstone ruin of a Benedictine priory built around the same time as Durham Cathedral, now roofless, weathered, I felt the ethereal, timeless quiet that St. Aidan must have cherished.

Bede spent his life at St. Paul’s monastery at Jarrow (about 18 miles northeast of Durham). The monastery was built about a generation after Lindisfarne by Benedict, the son of a local noble family who went to Rome and subsequently adhered to the pope’s version of Catholic theology. The stone walls, an advance upon Lindisfarne’s oak and thatch, were built by masons brought in from the Continent. These have been incorporated into the church that stands on the site, and the rough authenticity of the modern church (in a curve of the Don River before it empties into the Tyne) is beautiful and a bit forbidding.

Grey Street in Newcastle-on-Tyne. Credit Andrew Testa for The New York Times

A few hundred feet north of St. Paul’s, across the green, is Bede’s World, a museum devoted to replicating life in the eighth century. The main building, an orderly and active museum on one floor that displays artifacts and information about Bede and also hosts lecture series and art displays, is backed up by a reconstruction of a small farm consisting of thatched buildings, handmade fencing and plants and animals typical of the period. One herb nicely grown out (though not flowering) in early March was woad.

The animals are as authentic as possible, and fascinating — not only the furry blond hog and the bossy geese, but also the very active and curious sheep, which stood on the hillside in their small pasture and stared at visitors.

If you want to escape the Dark Ages, you may cross the Tyne and drive west about eight miles to Newcastle-on-Tyne, which is perched on the hills above the river. The oldest structure in town is The Keep, a stone replacement for a wooden fort that was built about the same time as Durham Cathedral and the priory ruins at Holy Island. But the really alluring part is 800 years newer than that: Grey Street, built in the 1830s. It curves downhill to the river from Grey’s Monument and is widely considered to be one of the most beautiful streets in England, with its graceful pale, elegant buildings; for a time Newcastle was one of Britain’s most prosperous cities, thriving on the mining of coal and the building of ships.

As you walk down Grey Street to the quayside, admiring the mix of old buildings and new, sharply delineated in the northern light, you may not recognize conversations you hear as English: Newcastle is famous for its local Geordie accent, said by linguists to be as close to original Anglo-Saxon pronunciation (that is, intransigently unaffected by Norman French or Viking Scandinavian) as any dialect in Britain.

Across the Tyne from Newcastle is Gateshead, originally the site of a Roman settlement, now the refurbished home of the Gateshead Millennium Bridge and the Sage Gateshead, a sinuous silver music performance space that opened in 2004. The Baltic Center for Contemporary Art, opened in the mid-1990s, is a redesigned and repurposed flour mill from the 1950s that showcases sometimes controversial art and artists. In 2011 it hosted the Turner Prize Exhibition.

Along the A1 highway (also known as the Great North Road) back to Durham, my companion pointed out Antony Gormley’s “Angel of the North,” just outside Gateshead. This 66-foot-tall male figure with a 177-foot wingspan is angelic, indeed, in a rusted, imposing and defiant way. Traffic was slow. The Angel, now 16 years old, sparked our conversation about how long it took Newcastle and the rest of the Northeast to recover from Margaret Thatcher’s battle with the coal miners’ union.

My companion told me that the Northeast continues to be overlooked. Although the highway needs to be widened, the Conservatives will never do it, because the Northeast always votes Labour, and Labour will never do it, because no matter what, they can count on the Northeast to vote for them. I took this political indifference personally — four days of exploration and admiration was shading into love.

Back in London, I could feel my resurrected Anglophilia slipping back into neutral, though. A city is a city in spite of the street names that enchanted me in high school and college. Even the very elaborate, informative and sold-out exhibition at the British Museum of Viking artifacts from all over northern Europe failed to move me. The artifacts in “Vikings: Life and Legend” are rich and plentiful; the reconstruction of an enormous warship, startling. But everything seemed domesticated. What was missing was the light, the space, the sharpness and fragrance of the air.

For real Anglophilia, I thought, you should be driving from the Durham railway station, just before twilight, up North Road, Potters Bank and Elvet Hill Road, narrow, green, damp, mysterious, arriving at the top in time for one last look at the ancient world that still lives in the landscape there.

Jane Smiley’s new novel, “Some Luck,” will be published in October.