| OBC Connect

A site for those with an interest in the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives, past or present, and related subjects.

|

| | | Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history, |  |

| | | Author | Message |

|---|

Jcbaran

Posts : 1620

Join date : 2010-11-13

Age : 73

Location : New York, NY

|  Subject: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history, Subject: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history,  6/2/2014, 12:16 am 6/2/2014, 12:16 am | |

| Bookshelf - WSJ - Book Review: 'The People's Republic of Amnesia' by Louisa Lim & 'Tiananmen Exiles' by Rowena Xiaoqing He

For younger Chinese today, the Tiananmen Square massacre is a story 'made up' by the Americans—or if anything did take place it was 'a CIA conspiracy.' - By Benjamin L. Read

May 30, 2014

A quarter-century has passed since the 1989 movement that shook Beijing and almost brought down the ruling Chinese Communist Party. Yet the passage of time has not necessarily made it easier to grasp the full dimension of the six weeks of protests around the country and the brutal suppression that began on June 3.

The university students who formed the backbone of the movement are now well into their mid-40s, and many Tiananmen veterans have published memoirs. Yet the supremely photogenic and emotionally stirring movement lends itself more to romanticization than clear-headed analysis.

The People's Republic of Amnesia

By Louisa Lim

Oxford, 248 pages, $24.95

Tiananmen Exiles

By Rowena Xiaoqing He

Palgrave Macmillan, 212 pages, $29

More daunting is the vacuum that surrounds the topic in the country where it occurred. The Chinese authorities have been remarkably successful in blotting out the public memory of the events, in propagating misinformation about the movement and in supplanting the protesters' regime-challenging, pro-democracy nationalism with a populist, regime-supporting, xenophobic nationalism. Within China today, large numbers of people are wholly ignorant or only dimly aware of what happened in 1989.

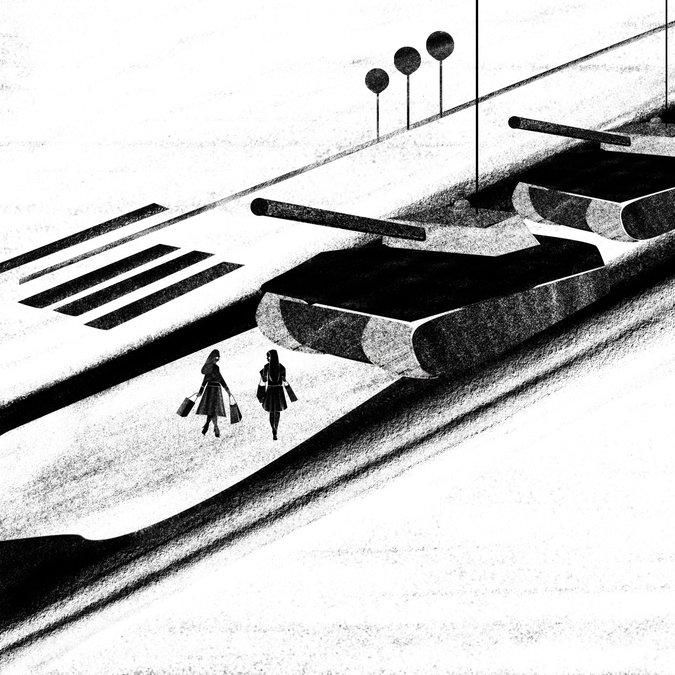

In "The People's Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited," Louisa Lim visits four of Beijing's top universities and confronts students with the iconic photograph of "Tank Man," the lone, anonymous figure who blocked a column of tanks in central Beijing in defiance of the crackdown. "Out of 100 students" in her furtive survey, she writes, "15 correctly identified the picture."

It is common in China to deny that any atrocity happened at all. In "Tiananmen Exiles: Voices of the Struggle for Democracy in China," Rowena Xiaoqing He describes young people insisting that "no killing ever took place," that "the massacre was just a story that had been 'made up' by the Americans" or that if anything took place it was "a CIA conspiracy."

Others justify the June 4 massacre in ways that parallel the government's position. Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba, the e-commerce giant with an upcoming IPO, said last year that Deng Xiaoping's unleashing of the People's Liberation Army on the demonstrators was a "cruel" but "correct decision." This sentiment is commonly heard in private homes in China, and Ms. Lim's campus conversations confirm that the younger generation has internalized the party line.

Both of these books grapple with this poverty of accountability and its implications. Ms. Lim, an NPR correspondent, presents a sequence of sensitive, skillfully drawn portraits of individuals whose lives were changed by 1989. Her first chapter nimbly reverses the usual perspective by profiling Chen Guang, who as a frightened 17-year-old soldier participated in the clearing of Tiananmen Square. He is now an artist obsessed with painting images related to the trauma—including renderings of the souvenir watch given to all the troops who helped impose martial law. We meet Zhang Ming, one of the student leaders who suffered prison and torture. (Force-fed milk while on a hunger strike, he now shuns solid food and maintains an all-milk diet.) He dabbles in business projects, focuses on raising his young children and refrains from political entanglements. He finds hope in the gradual evolution of the party and the rise of its newest cohort of technocratic leaders.

Ms. Lim visits the homes of two women who lost teenage sons to the massacre and coped with their grief by founding Tiananmen Mothers. Despite heavy pressure from the state, this organization has compiled a roster of the crackdown's victims and demanded compensation. She drops in on the brashest movement leader, Wu'er Kaixi, who fled China after the demonstrations and has had a checkered career. Under the eyes of a government surveillance team, Ms. Lim chats at a Beijing McDonald's with octogenarian Bao Tong, a former mainstay of the Communist Party's reformist faction and the highest-ranking official who served jail time after the crackdown. These portraits show us how the party tightly constrains those who defy it, but they also depict determined resistance and even suggest an optimism among those most directly affected by the events of 1989.

China is today a society mesmerized by wealth, and the post-Tiananmen generation is bent on getting ahead. Ms. Lim profiles a college student who has abandoned political questioning in favor of faith in the party and a 32-year-old used-car dealer who joins a rowdy but state-approved demonstration outside the Japanese embassy during tensions over the Senkaku Islands. These are by far the more typical Chinese citizens, products of the shackled educational system and filtered media environment. Incuriosity and indifference to historical truth abound in a China that sees itself as hurtling toward the future.

The "Great Forgetting," as Ms. Lim terms it, started, of course, with the coercion of the state, its carrots and sticks, and its vast manipulation of information, from editing textbooks to censoring the Web. But she discerns secondary factors as well. Parents shield children from their own firsthand knowledge of what happened. She notes that Mr. Zhang—once No. 19 on the government's most-wanted list—never brings up the movement with his younger wife. She and her friends have no interest in it. "The reason they do not like to talk about 1989 is not because it is a politically sensitive topic or because it makes them uncomfortable. It simply does not register."

An undercurrent of outrage animates the "The People's Republic of Amnesia." Ms. Lim is incensed that "the people themselves have colluded in this amnesia and embraced it." She confronts, for instance, a woman she meets at the daily dawn flag-raising ceremony in Tiananmen Square, asking whether she knew about the violence that had been wreaked along the avenue leading to that very spot. "Her face fell. I had cast a pall over the moment, behaving in the stereotypical way of the doubting Western media." Ms. Lim passes harsh judgment on some in China who pursue ordinary lives and work with or in the government.

Rowena Xiaoqing He, a visiting scholar and instructor at Harvard University who herself took to the streets during the uprising 25 years ago, is more specifically interested in the problem of the movement's exile and marginalization. Her book focuses on the lives of three student leaders who now reside abroad: Shen Tong and Wang Dan, well-known figures from the Beijing protests, and Yi Danxuan, a leader of the demonstrations in Guangzhou (the last two served time in jail for their activities).

Made up mostly of annotated transcripts of interviews, "Tiananmen Exiles" conveys the difficulty of maintaining a political movement far from a country in which you are "like ghosts or invisible men." The author draws the exiles out on such themes as the meaning of "home" and the tensions between maintaining political commitment and pursuing private fulfillment. Mr. Shen, for instance, found that the violent nightmares he endured for years ended soon after the birth of his first child, but he is uneasy about his choice to take time off from politics in order to provide for his family. The relationships of these exiles with their parents and the way their childhoods helped set them on the risky path of activism—Mr. Yi developed a rebellious streak when he was not allowed to date his high-school girlfriend—are revealingly explored.

In the end, though, any detailed sense of their political action during the long years in exile remains elusive. While free from any immediate threat of harm, Ms. He's three grown-up student leaders—she describes them as "children in adulthood"—endure the same vexations as Ms. Lim's Tiananmen survivors, including internecine squabbles with other dissidents, the unfinished nature of their cause and isolation from the mainstream.

Ms. He is devoted to keeping alive the 1989 "dream." Both Messrs. Yi and Wang object to this term as overly romantic. "I think we are no longer at an age to dream," Mr. Wang says. "We are no longer the children of Tiananmen." In one way or another, the exiles have decided that they need to take care of themselves and their loved ones rather than pursue their cause single-mindedly.

Both these books enhance our sense of the human costs of suppressing the past, of dulling the young's understanding of their world and capacity for critical thought, of severing people from a homeland that they yearn for—and of trying to pretend that none of it is happening.

What might it look like if the Tiananmen exiles were free to return to China without forsaking politics or if a free discussion of their struggle were to become possible there? Neither book speculates, and we are unlikely to know anytime soon. In time, the events of 1989 may be treated like the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s and early '70s—itself the subject of state-sponsored amnesia and the source of a wave of émigrés. That trauma has slowly become more available for research, debate and efforts to work toward the kind of historical accounting that the people of China so need and deserve.

In the meantime, the Tiananmen Mothers still await a response to their demands for justice, while most in China remain unaware that they exist.

—Mr. Read, an associate professor of politics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, is author of "Roots of the State: Neighborhood Organization and Social Networks in Beijing and Taipei." | |

|   | | Jcbaran

Posts : 1620

Join date : 2010-11-13

Age : 73

Location : New York, NY

|  Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history, Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history,  6/2/2014, 12:52 am 6/2/2014, 12:52 am | |

| I am going to add this here. This is an academic / scholarly book I doubt any of us will buy or read, but it's worth noting. File this under - myth making, creating a central acceptable and censored narrative, imperial control of religion and story, etc. Important if we want to know what is true and what is storytelling..... does it matter? yes, it matters very much

The History of Chinese Buddhist Bibliography: Censorship and Transformation of the Tripitaka

by Tanya Storch

Publication Date: March 25, 2014 - Price $104.49 - from amazon.com - so none of us will buy this.

"This clearly organized, well-researched book on the medieval catalogs of Buddhist writings in China illuminates the shaky foundations of modern Buddhist research. Storch exposes how the Chinese Buddhist corpus was shaped-and even censored-by generations of catalogers, the guardians of the canon. At the same time, Storch probes the catalogs for what they reveal about standards of authenticity; the assignment of value to some scriptures over others; and the history of books, libraries, and learning in pre-modern China. Moreover, Storch argues convincingly that the history of Chinese Buddhist catalogs should be incorporated into comparative discussions of scripture and canon in world history. As the first general study of Chinese Buddhist bibliography in English by an author who demonstrates a thorough command of the material, this book is the first place scholars should turn to for information about the structure and formation of the Chinese Buddhist canon. This book deserves a place on the bookshelf of every specialist in pre-modern Chinese, Korean, and Japanese Buddhism." - John Kieschnick, Stanford University

"This volume brings forward the importance of the cataloging of the many versions of the Chinese Buddhist canon. Given that these compilations are the source for much of the written history of Buddhism in East Asia, they deserve the careful study that has been given to them by Tanya Storch in this book. Her research advances the understanding and provides much new data about this genre of literature and its impact on Chinese religion and culture." - Lewis Lancaster, University of California, Berkeley

"Offers insight into wide-ranging issues of how religious ideas are transmitted between cultures. Although the focus here is on the ways in which Buddhism, in both oral and written forms, was assimilated into Chinese literary society, Storch's comparative approach will also be of interest to scholars specializing in the comparative analysis of sacred scriptures." - E. Ann Matter, University of Pennsylvania

"Cataloging is an essential step toward canon formation in East Asian Buddhism. However, current scholarship has not yet revealed the mysteries behind the collection of the enormous corpus of Buddhist texts, which is called the Buddhist canon, let alone the process of catalog making. Dr. Storch's work is pioneering in this direction and touches the core of the rich textual tradition in East Asian Buddhism. In addition, her meaningful contribution will be of interest to researchers of a global history of scriptural catalogs because she brings in a comparative perspective to the subject matter and puts the Chinese Buddhist catalogs on a par with the Confucian textual tradition and Western cataloging practices. This book is highly recommended for scholars and students studying Buddhism, history of the Chinese book, and comparative religion." - Jiang Wu, University of Arizona

"This highly accessible book is not only helpful to the nonspecialists in Buddhism but also to Buddhist scholars who are interested in how and why differing versions of the Buddhist canon came into existence. Much Buddhist sectarianism stems from different assessments of what should be counted as a reliable Buddhist scripture. This account of the long and complex history of Chinese Buddhist ideas about what should be included in a catalogue of authentic Buddhist scriptures sheds much light on the process of canon formation in Buddhism. It also demonstrates that Chinese Buddhists played a leading role in dividing Buddhism into so-called 'Hinayana' and 'Mahayana,' which is at the root of much Buddhist sectarianism. - Rita M. Gross, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire | |

|   | | tufsoft

Posts : 67

Join date : 2011-06-03

Age : 75

Location : ireland

|  Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history, Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history,  6/2/2014, 2:31 am 6/2/2014, 2:31 am | |

| I suspect that one reason people in China don't talk about Tiananmen much is that the material goodies they yearned for have mostly been delivered by the CCP. In more than ten years in China I only met one person who wanted to talk about it, although plenty of people wanted to talk about the Cultural Revolution and the hardships they endured at that time. Tiananmen nowadays is mostly an industry for western academics and professional exiles. Of course I don't support the shooting of demonstrators and the imprisonment of political dissidents but that's very easy for me to say sitting in a peat bog in Ireland, what if I had to deal with those problems myself? Look at what's happening in Thailand - what if that was China? 1.2 billion people. These things are not as easy as knee-[banned term] political commentators like to make out. | |

|   | | Jcbaran

Posts : 1620

Join date : 2010-11-13

Age : 73

Location : New York, NY

|  Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history, Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history,  6/4/2014, 10:22 pm 6/4/2014, 10:22 pm | |

| complex issues no doubt. the focus - for the purposes of this forum - is how China has a long and well managed tradition of manufacturing history, re-writing it, censoring - and that's what happened with Buddhism in China. You lived in China, so you have your own experiences with this. Many stories now coming out are saying most younger people have zero knowledge of what happened and there is certainly no open discussion. There is one official story allowed.

It is certainly a huge accomplishment to bring so many people out of poverty and create a modern nation - no doubt - and rigid and long-term suppression of all forms of freedom and critical thinking is and will have severe negative consequences. | |

|   | | Jcbaran

Posts : 1620

Join date : 2010-11-13

Age : 73

Location : New York, NY

|  Subject: from a journalist based in China Subject: from a journalist based in China  6/4/2014, 10:24 pm 6/4/2014, 10:24 pm | |

| Tiananmen, ForgottenBy HELEN GAO JUNE 3, 2014 - NYTIMES Credit Michela Buttignol BEIJING — I don’t remember the first time I heard the term liu si — June 4 — which is how the Tiananmen protests, the widespread demonstrations in 1989 that ended in bloodshed, are referred to in China. It was perhaps sometime around 2003, when I was 15 or 16. The term was probably uttered at the dinner table by one of my parents, both of whom were on the Avenue of Eternal Peace, the street in front of Tiananmen Square, on that night. They bore witness to the senseless killing, a memory that has haunted them ever since. I do remember the first time the topic came up in conversation with my Chinese peers. On June 4, 2009, the 20th anniversary of the crackdown, I was shopping with a friend at a convenience store near Tsinghua University, when she, a junior at the university, turned to me, next to a shelf of colorful shampoos and conditioners. “Some people have been talking about this incident, liu si,” she said. “What was it all about?” Twenty-five years after the massacre, the topic remains taboo here. I try to piece together the events of that spring through underground documentaries, foreign reports and conversations with my parents. Yet the more facts and anecdotes I gather, the more those crowds and gunshots seem unreal, like tragic scenes from an old foreign film. To my generation, people born in the late 1980s and 1990s, the widespread patriotic liberalism that bonded the students in the early 1980s at the start of the economic reform period feels as distant as the political fanaticism that defined the preceding decades. Chinese leaders, having learned their lesson during the Tiananmen protests, have kept politics out of our lives, while channeling our energies to other, state-sanctioned pursuits, primarily economic advancement. Growing up in the post-Tiananmen years, life was like a cruise on a smooth highway lined with beautiful scenery. We studied hard and crammed for exams. On weekends, we roamed shopping malls to try on jeans and sneakers, or hit karaoke parlors, bellowing out Chinese and Western hits. This alternation between exertion and ennui slowly becomes a habit and, later, an attitude. Both, if well-endured, are rewarded by a series of concrete symbols of success: a college diploma, a prestigious job, a car, an apartment. The rules are simple, though the competition never gets easier; therefore we look ahead, focusing on our personal well-being, rather than the larger issues that bedevil the society. Many of my Chinese peers, for example, are unfamiliar with the stories of Ai Weiwei, whose courageous struggles against the state are better known among my Western friends. Topics such as the religious repression in Tibet and military crackdowns in Xinjiang barely make a dent on the collective consciousness of my generation. The few times that I’ve spoken to my Chinese friends about the self-immolations among Tibetan monks, I’ve been met with looks of surprise. A few seconds later, some have asked, “Why?” Perhaps nowhere is this indifference toward politics and civil rights more pronounced than in the insouciance of young people about the Communist Party’s attempts to expunge historical truths from public memory. The majority of my generation still believes, for instance, that the war against Japanese invasion in the 1930s and ’40s was fought primarily by Communist soldiers, while the Nationalist army “passively resisted the Japanese and actively combated the Communists,” as told in my high school history textbook. The Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution mean little more than the scanty facts we had to memorize for the national college entrance exam. The massacre of 1989, the most recent tragedy of all, is also the most forgotten: One of the first victims of the massacre, Jiang Jielian, was a junior at my high school. While his mother, Ding Zilin, and other mothers of the victims, are still seeking justice for the death of their sons and daughters, Jiang’s name is known to few of my classmates. The party is responsible for distorting my generation’s understanding of history through state education and blocking our access to sensitive information. Yet even those who are well-aware of the state’s meddling make little effort to seek truth and push for change. When I returned to China after finishing college in the United States in 2012, I was shocked to discover how few of my friends use VPN, software that allows one to scale China’s Great Firewall and access blocked sites like Twitter and other media platforms. Well-educated and worldly, they nonetheless see censorship more as a nuisance of daily life, something to be begrudgingly endured, rather than an infringement on their freedom of speech. “I have to keep an eye on my watch when I browse foreign websites,” a friend at Peking University told me. Contrary to academic institutions worldwide that aim to make information available to students and scholars, Peking University charges an hourly fee for on-campus access to foreign websites. “It’s a little annoying, but I don’t browse them often anyway,” my friend explained. “Except when I check my email.” If the previous generations learned the cost of political transgression through persecutions and crackdowns, today’s youth, especially those from elite backgrounds, instinctively understand the futility of challenging the system. After all, most of the time, power interferes with our personal lives only in the form of nettlesome restrictions. These inconveniences — from censorship to the vehicle license lottery, a system that distributes a limited number of license plates to a huge number of new drivers who apply each month — feel not unlike the dogmatic words of Marxist philosophy in our school textbooks, which we mock in private but dutifully memorize and copy onto exams. Rebelling against these hurdles seems both naïve and unproductive — an understanding that the system has inculcated into us early on — as it would likely achieve little. Circumvention and compromise help us move forward, in a society where the price of falling behind is surely greater than the minor harms in our daily lives caused by state power. Over time, such an approach is rationalized, and even defended by the very group of young elites who in previous generations have been the most passionate advocates for change. Last October, Xia Yeliang, an economics professor at Peking University, was dismissed from his job after making bold demands for political change. The school insisted that Mr. Xia was fired for poor teaching skills. When the news broke, scores of university students rushed to defend the school’s claim on social media from what one called “Western media’s typical tactic to smear the image of China.” “Outsiders may pay more attention to freedom of speech, but students here care more about academics and teaching,” a friend who was a student at the university said to me at the time. “Neither side should impose its opinion on the other.” Today, most of my high school friends, having graduated from top Chinese universities, are working at state banks and government-owned enterprises. Several have passed the competitive civil-service exam and landed cushy positions in government. Nationwide, China’s best and brightest are chasing the stability and prestige offered by the state system: A survey conducted by Tsinghua University reveals that state-owned enterprises and government organs rank as the two most desirable destinations for university graduates. Outsiders, as my Peking University friend might say, may lament the contrast between the conservative outlook of today’s Chinese youth and the unbounded liberalism of the Tiananmen generation. But among the minority of my peers who are familiar with liu si, the rosy romanticism on the square in 1989 takes on a different hue today, when viewed in the fluorescent light of a government office cubicle. In a recent conversation with a high school friend, who is now an editor at People’s Daily, the flagship of the state-run media, he brought up the subject of Tiananmen. An avid follower of Western news and user of Facebook, he shrugs off the urgency for Chinese society to revisit the event. “What do you think it can bring us, to resurrect liu si?” he asked. “Nothing is going to change. We have to move forward.” Helen Gao is a journalist based in Beijing. | |

|   | | tufsoft

Posts : 67

Join date : 2011-06-03

Age : 75

Location : ireland

|  Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history, Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history,  6/5/2014, 2:24 am 6/5/2014, 2:24 am | |

| There has been Tian’anmen fever over here for the last week, and having lived in China and having lots of friends there it has been very painful for me to watch. A major newspaper published an article about it in which four different writers all approached the topic from the point of view that Tian’anmen was the suppression of democracy in the bud by the forces of vicious repression. Three of them were exiles who had either been involved in the rebellion themselves or relatives of people who had been involved, and one was an American academic who had published a book of documents which were supposedly leaked from inside the Chinese government, except that nobody can actually verify their authenticity, the Chinese claim that they are false. I don’t have any view on the matter because I don’t know.

None of the writers had any idea what would have happened if the rebellion had continued, the American gentleman, when asked, said that maybe China would still have experienced economic development, but he didn’t know.

Below the line, everyone, to a man, hailed the Tian’anmen demonstration as a Chinese Spring that had been put down by the iron heel of Deng Xiaoping. Everyone, that is, until about the 40th comment when a Chinese woman (Taiwanese actually) came on and made some salient points from the point of view of actually knowing something about Tian’anmen, such as that the political situation was very dangerous and that nobody knew who was funding the demonstrations, of course she was hounded out and pretty much accused of being a jackbootist for even thinking about it.

I can pretty much guarantee that hardly any of the bloggists know the first thing about China, about the Opium Wars, about the fact that China, until the end of World War 2 was occupied by the British, the Soviets, the Germans, the Japanese (who massacred millions of people and conducted experiments on living people like the Nazis), that until 1971 the UN did not recognise the PRC as the legitimate China. In 1989 the Chinese government had very legitimate reasons to fear that their whole project could have been overturned by a few student radicals with no experience of government and serious political program at all. If you had been Deng Xiaoping, what would you have done?

Yes, Chinese people are brainwashed to a certain extent, or to put it another way, they have their own narratives which are not the same as ours. Do you seriously think that Americans and Europeans are not brainwashed? Because as far as Tian’anmen is concerned it seems that there’s only one narrative allowed at the present time, which is that Tian’anmen was the bursting forth of forces of freedom and light and Deng was the evil villain who nipped it in the bud. And, of course, no actual knowledge of Chinese history or culture is required to subscribe to this narrative, entry is free and the rewards, in terms of smug self-satisfaction, are boundless, are they not?

I don’t like the fact that people were killed in Tian’anmen, in 1989, I don’t support the use of arms against civilians, and there are some aspects of China’s development that I personally don’t feel altogether happy about, but I know from my experiences of living in China, sometimes living and eating with peasants who live a whole family to one room and save the bones of a fish from one meal to the next, that they want development, they’ve been watching Hollywood movies and American TV shows and they want what we’ve got and it’s not my place to tell them what they should want. But I do recognise that there was a real and pressing problem facing China in 1989, and all I can do is repeat my question to you and anyone who thinks it’s so easy, if you were Deng Xiaoping, what would you have done? Would you have rolled over and handed the government to someone else? Was the fact that you didn’t do that entirely down to personal vanity? Don’t forget that Deng was largely responsible for the modernization of China, largely following a template outlined in Sun Yatsen’s book “The Modernization of China” which he wrote out of years of research in the British Museum in London, and which is now on Gutenberg.

Yes, there are unpleasant side-effects of political indoctrination but political indoctrination happens everywhere, given time the Chinese will develop more of the civic freedoms that people take (or have taken) for granted in the west (though some of these are being eroded now). But in many respects, they still trail us by several years. It’s only since 1949 that the government has been able to make a concerted effort to unify the language so that people in different regions can even speak to each other.

You know what? I really don’t think there’s any point in speaking to people who boast about how others are brainwashed and are completely blind to the fact that they’re brainwashed themselves! How would you like it if I came on here and started fulminating about all the people your own government killed in Iraq, for instance? | |

|   | | Stan Giko

Posts : 354

Join date : 2011-06-08

Location : Lincolnshire. U.K.

|  Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history, Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history,  6/5/2014, 4:05 am 6/5/2014, 4:05 am | |

| " How would you like it if I came on here and started fulminating about all the people your own government killed in Iraq, for instance? "

I`d get bored pretty quickly......it`s a perfectly valid point ! plenty of brainwashing in the west and

everywhere else, come to think of it. How free and unbiased are the media in the west ?

How free and unbiased is anyone ? I would say though, that if the state gets to control the internet,

then personal liberty is on very precarious ground. | |

|   | | tufsoft

Posts : 67

Join date : 2011-06-03

Age : 75

Location : ireland

|  Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history, Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history,  6/5/2014, 7:46 am 6/5/2014, 7:46 am | |

| Thank you for your courteous and measured response.

Of course personal liberty has boundaries everywhere, I don’t know how to answer you really except to say that China is like the US or anywhere else, there are a wide range of people holding a wide range of views, including (and this may actually amaze some westerners) people who actually support their government. There are some restrictions on the internet and sometimes they seem tedious and pointless, but most people can live with them and know how to work around them when they can’t. But the western newspapers seem to give the impression that everyone in China wants a free internet tomorrow, I certainly never got the impression that was the case. Chinese people are a lot more sensitive to the powder kegs waiting to explode beneath them than westerners, and it might surprise some people that they do not universally relish the prospect of their country erupting into anarchy. I haven’t actually conducted a vox pop about the internet as it never really seemed to be an issue, but one issue that did interest me was the censorship of “Lust, Caution” which came out while I was there. The Chinese censor demanded some cuts to the Chinese version (as indeed Ang Lee must have known they would), it was about a minute and a half of lovemaking, because at present nudity is not shown in Chinese films or on Chinese television. I talked to several friends about it and also to quite a few people in the film industry, and none of them disagreed with the stance their government had taken and in fact most of them expressed very strong agreement with it. But as I said, there is a wide range of people in China and a wide range of views and a lot of Chinese either went to Hong Kong to see the uncut version or watched the forbidden clips on the internet. After a couple of months, of course, it was in all the pirate DVD shops anyway. It’s a different culture, why is this so hard for people to understand? Not inferior, different.

I guess the point I am trying to make is that I despair when I see the biased portrayal the western media give of China, that because there are internet restrictions everyone in China must be champing at the bit for a free internet, because there is censorship everyone in China must be foaming at the mouth for video sex, actually there are a lot of people in China, older people, parents, people who lived though the famines of the cultural revolution (my accountant who was in Beijing at that time told me he used to eat the leaves off the trees), many people who although they grumble about officialdom and have issues with the government still support the broad path their country is taking and value the hard won stability and economic growth they have achieved.

In my opinion, the way the UK newspapers behaved over the anniversary of Tian’anmen was really very cynical, a cynical attempt to use other people’s tragedy as a pawn to further their own interests. If they can blow the whole thing up again, it’s no skin off their nose if there are rivers of blood in the streets of Beijing. I really think people have lost their grip on reality here. And as for “my Chinese friend disagrees with me, boy is she brainwashed”, do I really have to dignify this with a response? | |

|   | | Sponsored content

|  Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history, Subject: Re: Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history,  | |

| |

|   | | | | Two current books on myth making, manufacturing history, |  |

|

Similar topics |  |

|

| | Permissions in this forum: | You cannot reply to topics in this forum

| |

| |

| |

|